Henry VI – Part Two

This is the second part of the story of the reign of Henry VI. You can read the first part at Henry VI Part One.

France

Truce between England and France ends

The truce, between England and France, signed in 1444, lasted until 1449, when it was broken by a foolhardy English raid into Brittany. When the English refused to pay reparations Charles VII declared war. By now the French armies were better organised and equipped and their commanders had learnt lessons the hard way through past English victories. The design and performance of artillery had progressed and cannons proved to be a crucial element in some of the forthcoming battles. And, the French people were now more nationalistic and tired of the seemingly unending conflict caused through English aggression.

England loses control of Normandy

By August of 1450 the English had lost the whole of Normandy. This catastrophic turn of events, brought about in part through help given to the French by the people of Normandy, was totally unexpected in England. In actual fact it should have come as no surprise. The English army in France had for some time been short of men and supplies. This was mostly due to the Crown now being in debt to the tune of £400,000 when its yearly income amounted to less than £30,000. Additionally, the English had met with most success when they were allied with the Burgundians; however, when the Duke of Burgundy sided with Charles VII, the English were far less likely to become masters of France.

The blame for the loss of Normandy fell upon the shoulders of the Duke of Suffolk. He had made enemies in all classes by his greed in amassing land and offices and the inefficiency of his administration. He was thought to have had a hand in the murder of Duke Humphrey, known to have given away the province of Maine, and believed to have been responsible for costly losses in France.

Murder of the Duke of Suffolk

Suffolk was impeached but the king saved him from a death sentence by sending him into exile. However, when he was crossing the Channel, an English warship took him onboard and two days later he was beheaded by a rusty sword. This is a sign of the lawlessness of the time, when a high-ranking member of the government travelling under the protection of the king could be summarily put to death. If the law and the king’s authority could be ignored then exactly whose word would be obeyed?

Hundred Years War ends

A year after the fall of Normandy it was followed by the loss of Gascony. An attempt in July of 1453 by Lord Talbot to retake Gascony ended in total failure. The English army was torn to pieces by entrenched artillery and Talbot himself ended up dead on the battlefield.

All that remained of the England’s once numerous possessions in France was Calais. 1453 marked the end of what became known as the Hundred Years War. It had been an on/off and up and down affair, started by King Edward III and lasting somewhat longer than its title.

The map shows the progress of the Hundred Years War at various dates. Light grey is land controlled by England, dark grey is Burgundy and yellow is France. Major battles are shown in red.

Though free from the English, generations had suffered through the privations caused by such a long war. It would take France some time to fully recover. When it eventually did so it would outstrip England in its power and world prestige.

Henry has a mental breakdown

In June and July King Henry had been spending some time in Wiltshire. Whilst there he had a mental breakdown. Whether or not this was due to the grave news from France is uncertain. The king’s memory failed, he couldn’t walk and he recognised no-one. Thus, England had lost not only France but its king.

Background to political intrigues and factions

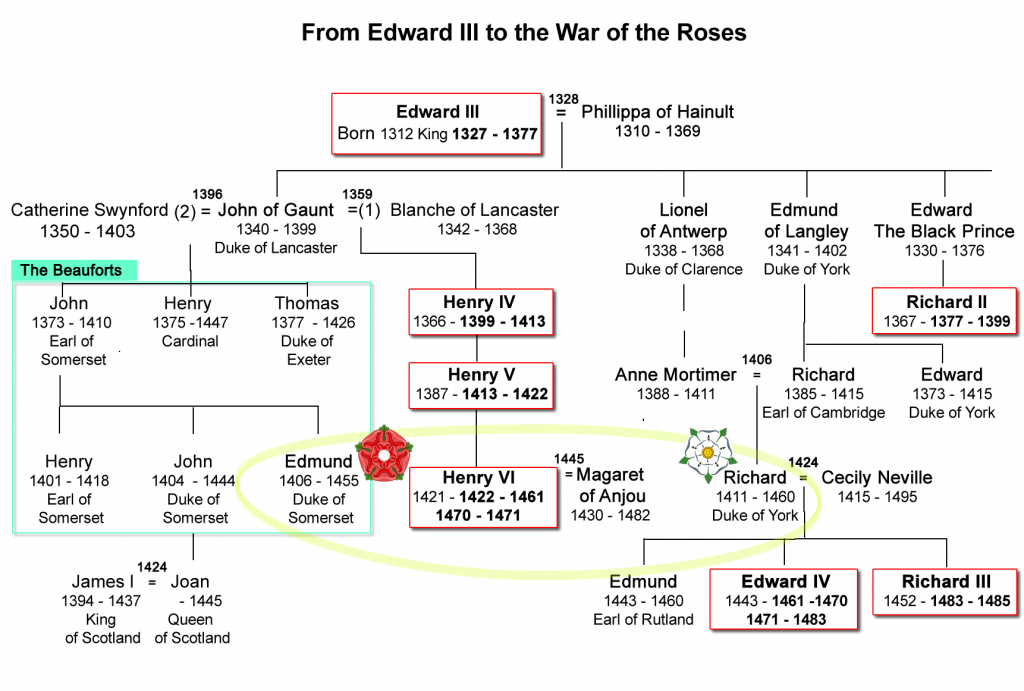

England was to become subject to a power struggle between the Lancastrian, Edmund Beaufort (Duke of Somerset), and the Yorkist, Richard Plantagenet (Duke of York).

The rivalry between Duke Edmund and Duke Richard was to be a leading cause of the Wars of the Roses.

Edmund, Duke of Somerset

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and son of King Edward III, had three sons with his mistress, Catherine Swynford. John eventually married his mistress and their children were legitimised. They were known as Beaufort, so-named after the castle in which they were brought up in France. When they grew up, the Beaufort men speedily became rich and powerful. Henry Beaufort became Bishop of Winchester, a Cardinal, and for a time he was Lord Chancellor of England.

Henry’s brother, John Beaufort (died 1410), was Marquis of Somerset and had two sons. His elder son John was Duke of Somerset until his death in 1444. His younger son Edmund was created Duke of Somerset in 1448.

John’s daughter, Jane, married King James I of Scotland and through them descend the Scottish royal line. The Beauforts descend directly from Edward III. However, by an Act of 1407 they were barred from succession to the throne.

Richard, Duke of York

Richard becomes Duke of York

In 1415 the Earl of Cambridge was executed for his role in a plot against Henry V; in the same year the Duke of York was killed at Agincourt. The dukedom of York eventually passed to Richard, the son of the executed Earl of Cambridge. However, being only a child in 1415, it would be some time before he took control of the land and wealth that went with the title. In 1417, the wardship of Richard was granted to Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland; in 1424, aged 13, Richard was betrothed to Cecily Neville, who was aged just nine. In May of 1426 he was knighted by John, Duke of Bedford, and formally restored to the duchy of York. In 1429 he married Cecily and on 12 May 1432 he came into his inheritance and was granted full control of the vast Yorkist estates.

Duke Richard becomes Lieutenant of Ireland

In Henry VI Part One, I gave details about the activities of the Duke of York, including his command of the English forces in France. By the time he returned to England in 1445, Duke Richard’s views on the poor conduct of the war and the corrupt members of the government were well known. In 1447 he was appointed Lieutenant of Ireland. After spending a good deal of time sorting out his financial affairs, he landed in Ireland with a small army in June of 1449.

The Beaufort faction no doubt thought that any influence he had in England or France would be diluted if he was packed off to Ireland. His appointment was for ten years, which would rule him out of any Office of State in England for a whole decade. He had distinguished himself in France during his tenure as commander of the forces there, and his administrative and diplomatic skill over the Channel had proved to be second to none.

On his arrival in Ireland several Irish chieftains submitted to him and he gained the goodwill of the people by crushing some of the lawless elements. Once again, he had shown that he was a wise and capable leader of men. Many of those in high places had already taken note of Duke Richard’s strengths.

Uprising in Kent

In June and July of 1450 a rising took place in Kent, which the Lancastrians suspected had Yorkist support. Jack Cade, an experienced soldier, was the leader. After gathering together a very large following he marched on London and was admitted to the city.

However, after executing Lord Say, the Treasurer, the people of London turned against Cade. Those with him were granted pardons provided that they dispersed but Cade was pursued and killed. Above all, this highlights the level of discontent amongst ordinary folk.

Duke Richard returns to England

It was one thing to complain about the state of affairs in England but leadership was needed to bring about change. In the divisive politics of England, Duke Richard had remained neutral but in 1450 he returned from Ireland without permission and landed on Anglesey. As the king had no children, Richard’s lineage gave him the right to be named as heir to the throne of England. Perhaps he was worried that Beaufort sympathisers would manage to annul the Act of 1407. If this happened then Duke Edmund would have a superior claim.

Duke Richard marched on London and on route many others joined him. After an unsatisfactory meeting with the king on 27 September, Duke Richard continued to recruit followers in East Anglia and elsewhere. At this time the violence was so bad in London that Duke Edmund, back in the city after the loss of Normandy, had to be locked up in the Tower for his own safety.

England divides into two factions

By now England had divided itself into two factions. Duke Richard’s platform was that of a reformer, demanding better government and the removal and prosecution of those responsible for the loss of English possessions in France. The other faction was supposedly that of the king but actually of the Beauforts. It now had Duke Edmund (Duke of Somerset) at its head and in control of the government and could be said to support the status quo. The growing animosity between the Lancastrians and Yorkists does in no way mean a dispute between two English counties. The north, including York, supported the Lancastrian cause whilst Yorkist support came from the midlands and south of England. However, there were some overlaps.

Duke Richard moves back to Ludlow

During a Parliamentary session in 1451 Thomas Young, a member of the Commons, proposed that Duke Richard should be declared heir to the throne. When Parliament dispersed Young was promptly arrested and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Some reforms were made in the name of Henry VI, which helped both to restore public order and improve the royal finances. Duke Edmund was released from the Tower in April of 1451 and given the lucrative position of Captain of Calais.

Duke Richard was popular with the merchant and lower classes. However, many of the important nobles were worried about his pretensions. Feeling that he lacked the necessary support he retired to his castle at Ludlow, on the border with Wales.

Richard marches on London

Disgusted by government’s failure to remedy its defects, in 1452 Duke Richard marched from Shrewsbury to London with a large army. However, the gates of the city were locked and he was refused entry. He then moved to Kent, perhaps hoping that the men who had supported Jack Cade would now rally to the Yorkist cause but this didn’t happen. Civil war seemed imminent. Duke Richard now had some nobles on his side but the powerful Earl of Warwick and others were with the king.

After several parleys at Dartford, Richard dispersed his forces and bowed down before King Henry. He assured him of his loyalty but at the same time demanded better government. The duke was taking a great chance, for this was an opportunity for his enemies to slay him. However, his enemies knew what his death could lead to.

King Henry forms new Council, led by the Duke Edmund

The cause that Duke Richard stood for was supported by the Commons and a huge section of the population of England; additionally, his young son (Edward, Earl of March) had a second army manoeuvring on the Welsh border. The eventual outcome was a promise by the king that a new Council would be formed and Richard would be a member. The Court had to choose who would be head of the Council. Queen Margaret, already antagonistic to anyone favourable to Yorkist policy, decided in favour of the Duke Edmund. For more than a year Edmund was head of affairs in both England and France.

Duke Edmund imprisoned

The loss of Gascony could have led to the immediate downfall of the Duke Edmund. However, he managed to hold on until December of 1453, when the Council ordered that he should be imprisoned in the Tower. When King Henry lost his mind in July the queen was pregnant. To many, this must have seemed nothing less than a miracle. With her husband totally unable to function as king, Queen Margaret hoped to be appointed Protector of the Realm. She was opposed by Duke Richard, who wished to be responsible for England whilst the king was incapacitated. In October the queen gave birth to a son.

Duke of York appointed as Protector of the Realm

In March of 1454 the Lord Chancellor (John Kemp, Archbishop of York) died and this made government in the name of Henry VI impossible, for only the king could appoint a successor. Despite opposition from the queen, the Duke Richard was appointed as Protector of the Realm and Chief Councillor five days after the death of Kemp. The post of Chancellor was given to the Earl of Salisbury (Richard Neville) and thereafter the Neville family would support the Yorkist cause. It is said that these changes led to an immediate improvement in the administration; one element that was particularly welcomed was the clamp-down on lawlessness

The lead up to the end game

King Henry recovers

At a time when most disputes had been settled and England seemed now to be enjoying a popular and fair government, in January of 1455 King Henry recovered from his spell of insanity. To quote one historian: if Henry’s insanity had been a tragedy, his recovery was a national disaster. With the king back at the helm, no time was lost in ridding the government of Duke Richard and his Yorkist supporters. Duke Edmund, who had been languishing in the Tower, was released and his influence over the king was as strong as ever. Edmund and Queen Margaret now ruled supreme. It was obvious that they and their adherents would attempt to bring down Duke Richard.

Yorkists defeat Lancastrians at St Albans

Duke Richard retired to Sandal in Yorkshire. He was joined by the earls of Salisbury and Warwick, together with several other nobles. Duke Edmund was denounced as the man responsible for the losses in France and it was said that he would now ruin England. Duke Richard and his supporters took up arms and marched south. Many more men, led by Yorkist sympathisers, headed to the pre-arranged meeting point of St Albans.

The king, queen, Somerset and others of the Lancastrian party, numbering less than 3,000 men, moved to meet them. The king’s army reached St. Albans first and set up a barrier on the main street. The Yorkists did not wait for reinforcements; instead, they advanced.

In the ensuing engagement Duke Edmund was killed. After being slightly wounded by an arrow the king took refuge in a house. The death toll amounted to no more than 300 (one account puts it as low as 50) but it included a high proportion of Lancastrian nobles.

The queen took sanctuary and the king was taken into the hands of the Yorkist leaders.

Duke Richard becomes Constable of England

However, the victors assured the king of their devotion. He was escorted to London and Duke Richard made himself Constable of England. The king was held prisoner and when Parliament met in November it was announced that Henry had lapsed into insanity. Duke Richard took on the role of Protector but resigned the post when King Henry recovered early in 1456.

Uneasy truce

The Lancastrian party was still made up of the majority of English nobles and a few months after the St. Albans debacle they were as strong as ever. Attempts were made at conciliation but there were risings in various parts of the country and bloodshed was not unusual.

The years from 1456 to 1459 made up a period of uneasy truce. However, both sides must have realised that a settlement would eventually have to be made and this may well be through armed conflict. In 1459 fighting broke out again. A gathering at Worcester of armed Yorkists dispersed and the leaders fled when a royal army arrived. Perhaps not wanting to be responsible for a full scale civil war, Duke Richard retired to Ireland.

Duke Richard being named heir to the throne

July of 1460 marked the start of the real end game. Whilst Duke Richard was still in Ireland, Yorkist lords under the command of the Earl of Warwick came to grips with a Lancastrian army at Northampton. When the battle started Lord Grey, in command of a Lancastrian wing, went over to the Yorkists and this led to the royal army fleeing in panic. King Henry was captured again and taken to London. An agreement was reached through which Henry would remain king for life but when he died Richard of York would become king. This, of course, ignored the fact that Queen Margaret and her son were at liberty.

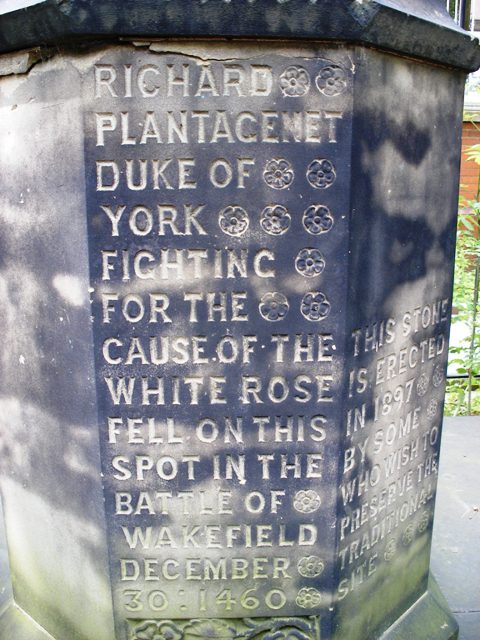

Duke Richard dies at the Battle of Wakefield

On 30 December 1460, Queen Margaret and an army raised in the north and in Wales met with the Duke Richard at Wakefield. Richard foolishly went into battle before his full force had arrived and suffered the consequences. The battle has been described as a massacre. Richard and his son Edmund (Earl of Rutland) were killed and the Earl of Salisbury was caught later and beheaded. Many old scores were settled before and after this engagement.

Richard’s son Edward, becomes Duke of York

However, the Yorkist cause was now taken up by a new generation in their twenties: the sons of the Dukes of York and Salisbury. Richard’s son, Edward, now became Duke of York.

Earlier in 1460 Roxburgh Castle in Scotland had been in the possession of the English for some time. Taking advantage of the civil war that had erupted in England, the castle was captured by the Scots.

Duke Edward’s first success

At Mortimer’s Cross near Hereford on 2 February 1461 the new Duke of York (Edward) had his first opportunity to exact revenge. Edward was victorious in a battle where no quarter was given. Amongst those executed in the aftermath was Sir Owen Tudor.

Lancastrian success at St Albans

On 17 February at St. Albans another battle took place. Duke Edward had been heading there to meet up with the Earl of Warwick. However, Warwick’s army was defeated before Edward arrived. Warwick and the Duke of Norfolk managed to escape but half the Yorkish army was slaughtered and many important captains put to death the following day. King Henry, who had been held by Warwick, was now back in the hands of Queen Margaret. Flushed with success and reunited with the king, the Lancastrians headed north.

Duke Edward marches on London and declared king

Hearing of the defeat inflicted on Warwick, Duke Edward was now heading for London; when he reached Oxfordshire he was joined by Warwick and the survivors from St. Albans. On entering London the Yorkists received an enthusiastic welcome. The pretext of acting in the name of the Crown would no longer suffice. They were nothing less than rebels and traitors to the present regime.

However, Duke Edward interpreted matters in a wholly different way. His father had been ruined and killed through his respect for Henry VI, who had proved time and time again to be unfit to be king. Therefore, Edward declared himself king and on 4 March 1461 he was proclaimed king at Westminster. This being the case, any Lancastrian supporter would be regarded as being guilty of treason.

King Edward IV marches north

Edward, now acknowledged as King Edward IV of England, marched north to meet what would be likely to be the largest Lancastrian army ever formed. The advance guard was beaten back at Ferry Bridge (now Ferrybridge) in Yorkshire and the Earl of Warwick was wounded. However, the bridge was eventually taken and the whole of the Yorkist army passed over.

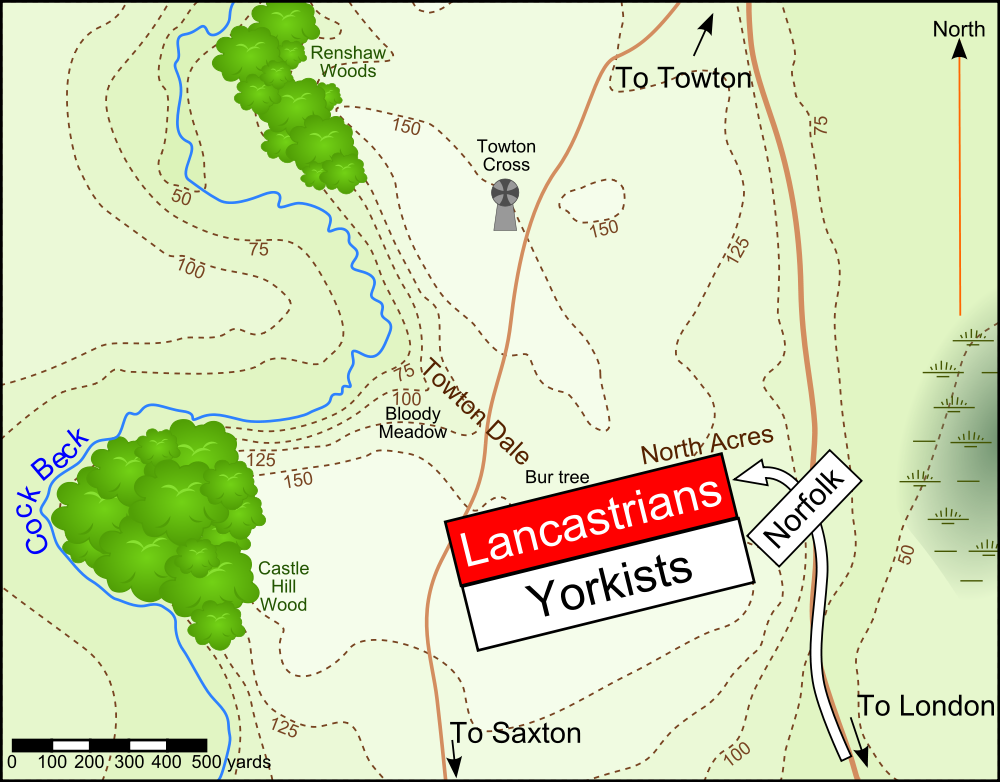

Battle of Towton

The following day, 29 March 1461, the two armies came together at Towton, which is near Tadcaster. Estimates of strength vary but the total number of men involved could have been as high as 100,000. Some sources say more but even with 100,000 the contours of the land at Towton would make it extremely difficult to direct a battle. The Lancastrians thought they had chosen a good position and the battle started before the Yorkist army was complete, as the Duke of Norfolk’s contingent was still on its way. The wind drove a blinding snowstorm into the faces of some of the Lancastrians. This not only covered the Yorkist advance but assisted the flight of their arrows.

For six hours the two sides fought with great bravery. The outcome hung in the balance until late afternoon, when the Duke of Norfolk arrived and his fresh troops fell upon an exposed Lancastrian flank causing men to start to retreat. The retreat turned into a rout as the Yorkist captains, knights and men-at-arms tore into the Lancastrians. Many were cut down and others who fled the field were drowned in the swollen water of nearby Cock Beck.

All the Lancastrian nobles and knights were killed at Towton, either in battle or through the executions afterwards. Queen Margaret and her son escaped to York, where they gathered up King Henry and then sped north and crossed the border into Scotland.

Signet ring at the British Museum

In the British Museum there is a very large and heavy gold signet ring on show in the same display case as the Fishpool Hoard (here’s my article on the Fishpool Hoard). The ring was found (during the 19th century or before) at Towton and might have belonged to Henry Percy (third Earl of Northumberland) who died during the battle or soon afterwards due to the severity of his wounds.

Edward crowned king

On 28 June 1461 Edward of York was crowned king at Westminster. The Yorkist triumph was heralded as being complete. Edward Plantagenet, head of the House of York, was now on the throne. However, the previous king, queen and heir to the throne were still alive. How long would such a strange situation be allowed to last?

Henry VI

Losing almost all England’s possessions in France

Henry VI reigned over a period during which England lost almost all its possessions in France. This could be put down as unfortunate. Had it not come about during his reign it would have been bound to happen later. Henry V had been very lucky to triumph against the odds at Agincourt. Later victories were with the support of Burgundy. When its duke changed sides and gave support to the French king it was just a matter of time before the English were pushed out of France. England was reasonably prosperous but it simply could not afford the huge cost of a prolonged war over the Channel. Parliament was aware of this fact but the ruling elite clung too long to the costly dream of the King of England also being King of France.

The Norman and early Plantagenet kings probably thought of themselves as more French than English. However, by the 15th century, even though they would still have liked to rule land across the Channel, kings would regard themselves as being purely English.

Misguided loyalties

Henry VI could be loyal but to the wrong people. When he came of age, his closest friends, the Beauforts and their associate the Earl (later Duke) of Suffolk, simply did not have the diplomatic and military skill that was required. Even when it became obvious that high positions in the government of England had fallen into the hands of men more interested in their own aims than the needs of their country, Henry did nothing to remedy the situation.

Duke Richard turned into an enemy

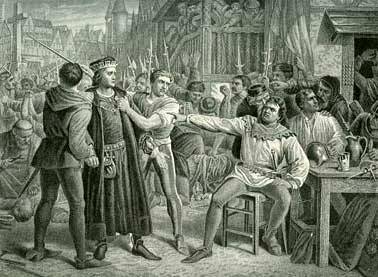

Henry VI (seated) while the Duke of York (left) and Duke of Somerset have an argument

Illustration from Henry VI in A Chronicle of England

Richard Duke of York comes over as a man who wished more than anything else for the removal of favourites and the reform of the government. During his two periods in France he had helped to finance the war effort with £38,000 of his own money. That was a colossal sum at the time. Even when armed conflict broke out in England he emphasised his loyalty to the king.

However, by that time Queen Margaret was the power behind the throne; instead of looking upon Duke Richard as a loyal subject she viewed him as a contender for the throne. By treating him as an enemy she eventually turned him into one.

Lawlessness

By the time Henry VI came to the throne the civil service had grown to be very large. It included clerks, lawyers, accountants and secretaries, together with their assistants and helpers. Even during the periods of strife, when there was contention and dispute about the highest offices of State, the civil service continued to function. However, in the wider sphere, the sheriffs and justices of the peace in the provinces were incapable of upholding the law against the many nobles who had their own private armies.

A Statute passed by Parliament in 1429 restricted the right to vote in parliamentary elections to men owning freehold property worth at least £2 per year in rent. This Statute came into being as it was thought men “of little substance or worth” should not be allowed to take part in something as important as election. The necessary amount of wealth, £2, would remain the same until the Reform Act of 1832.

Unsuited to the position of king

Had he had an elder brother then the man who became Henry VI would never have been king. He could have lived out his life contentedly, perhaps as a monk in one of the many religious institutions. Sadly, for himself and his country, he was the only son of Henry V. He became king when less than one year old. Therefore, a man totally unsuited to the stresses and strains of kingship came to rule over England, which at the best of times needed a strong hand at its helm.

Henry VI coins

For a guide on how to identify the various coin issues of Henry VI have a look at Quick Quiz #5 – Henry VI Issues