Henry II – his life and coinage

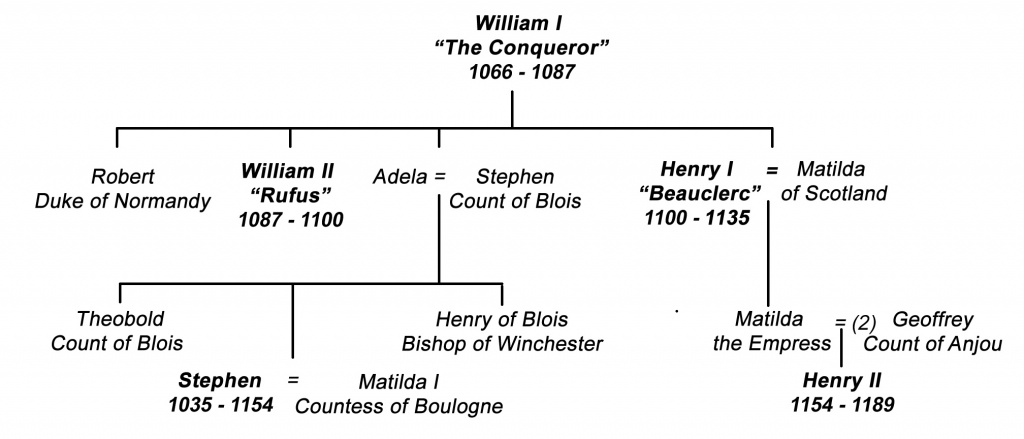

Henry Plantagenet was born at Le Mans on 4 March 1133. His mother was Matilda (daughter of Henry I of England and widow of the Emperor Henry V of Germany) and his father was Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou.

He was fortunate enough to receive a good education, which set him in good stead for the complex situations he would meet with as the eventual ruler of England and other territories.

Becoming king

Agreement with King Stephen

Henry’s first visit to England was as a child in 1142; later in the 1140s two attempts to gain the throne failed. Another invasion mounted in 1153 could have led to much bloodshed had not a settlement been reached, whereby Stephen would remain as king until his death and then Henry would take the throne.

Marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine

In May of 1152 Henry married Eleanor of Aquitaine, only two months after her marriage to Louis VII of France had been annulled. The couple would eventually have five sons and three daughters: William (died very young), Henry, Richard, Geoffrey, John, Matilda, Eleanor and Joan.

Crowned King of England

On 25 October 1154 Stephen died and on 19 December Henry Plantagenet was crowned as King Henry II of England. In 1150 Henry had become Duke of Normandy. On the death of his father in 1151 he became Count of Anjou and through his marriage to Eleanor in 1152 he gained Aquitaine. This made him the greatest ruler in Western Europe and his charters were issued under the titles of King of the English, Duke of the Normans and Aquitanians, and Count of the Angevins. Through war, luck and marriage he had come to rule over not only England but a huge slice of France.

Early years as king

Resolving problems from the past

Henry’s first task after he ascended the throne was sort out problems left by the reign of Stephen. Many castles that had been built without license were pulled down and royal authority re-established throughout most of the land. These two aims had been achieved by 1158, together with the overlordship of Scotland. In 1157 Northumberland and Cumberland were surrendered by Malcolm IV of Scotland to England and relations between the two countries remained stable for some time afterwards.

Unruly barons

An example of his early problems with unruly barons is Hugh Bigod, who was allowed to inherit the numerous East Anglian estates of his elder brother when he was drowned in 1120, along with Prince William (heir to the throne) and many other nobles. He also gained the lands of his aunt, Albreda, which were situated in Yorkshire and in Normandy.

On the death of Henry I, Hugh initially supported Stephen but proved to be untrustworthy. At one stage he seized the castle at Norwich but was forced to surrender when Stephen laid siege to the city. At the First Battle of Lincoln in 1141 Hugh fought on Stephen’s side but then took him prisoner. This led to Hugh being granted the earldom of Norfolk by the Empress Matilda. He also supported the notorious Geoffrey de Mandeville during his rebellion against Stephen in 1143-44. Henry II spent the first years of his reign restoring order to his kingdom but Hugh remained troublesome. However, he submitted when Henry marched into the eastern counties in 1157.

Wales

When it was believed that England had been subdued some of the Marcher lords who had been granted land on the frontier zones between England and Wales started to expand their territories. Henry himself attacked Wales in 1157, 1158 and 1163, in an attempt to bring the Welsh leaders to heal. However, bad weather and the ‘hit and run’ tactics of the native combatants prevented him from scoring a significant victory.

In a fit of pique Henry II ordered that the noses and ears of the daughters of Welsh princes, at the time being held as hostages, be cut off; this was followed by the blinding and castration of the girls’ brothers. Later, in 1175, Seisyll ap Dyfnwal of Gwent, together with his wife and small son, were among the Welsh victims of a massacre at Abergavenny. Henry then decided to simply let the Marcher lords do much as they pleased in Wales. The push into Wales by these lords would continue and eventually lead to many castles being built.

One commentator wrote: “They [the Normans] vigorously subdued the natives [of Wales], imposed law upon them in the interests of peace and made the land so productive that it could easily have been mistaken for a second England. There can be little doubt that the Welsh would not share this rosy view of their land being invaded.“

Ireland

Soon after Henry II came to the throne he discussed plans for an invasion of Ireland. However, Henry had more pressing problems to solve, so for the time being the plans were shelved.

Photo: Jay Galvin, CC By SA2.0

In 1169 Richard de Clare (full name Richard fitz Gilbert de Clare), who was the second Earl of Pembroke and later known as Strongbow, answered an appeal for help from the King of Leinster. This was the first time that English soldiers entered Ireland in force. Richard would eventually marry the daughter of an Irish king.

Two years later 400 ships transported Henry II and a large army over to Ireland. Henry claimed he had come to stop the Irish killing each other and most of the local kings submitted to him. After keeping the most important ports for himself (Dublin, Wexford and Waterford) he granted estates to his main followers. In the north John de Courcy took a large part of Ulster in 1177 and set himself up as an independent ruler. In the same year Henry made his youngest son, John, King of Ireland, hoping that Pope Alexander III would agree to him being crowned. Consent never arrived but John took up the title of Lord of Ireland and visited the country in 1185.

Nobles in England became the owners of great estates in Ireland, despite the fact that some of them never went there. Some English settlers, together with a few Welsh and Flemish, crossed the Irish Sea to farm, trade or manufacture goods of one kind or another. William of Newburgh, writing in the 1190s, said of the changing face of Ireland: “This marked the end of freedom for the Irish, a people who had been free since time immemorial. They had not been conquered by the Romans, but now they fell into the power of the King of England.”

European affairs

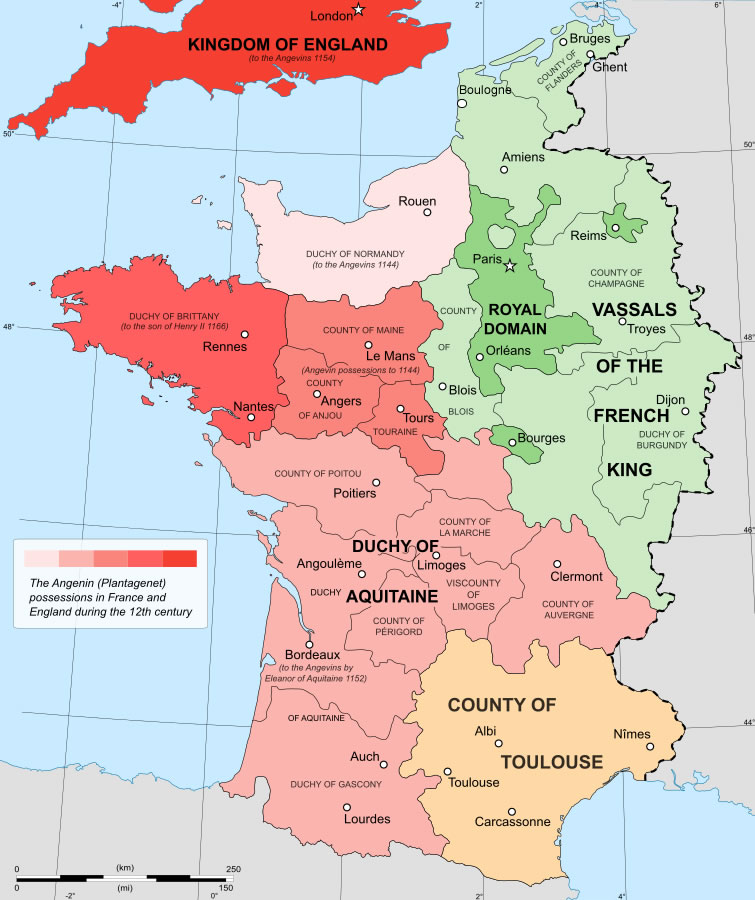

Henry’s Continental possessions would always take up more of his time and during a reign of 34 years; he spent 21 of them across the Channel.

by Amitchell125, CC BY-SA 4.0

Flanders

Soon after the start of his reign, Henry had expelled from the country all the Flemish mercenaries then in England, for he had heard that some of them were planning to kill him. The Count of Flanders (Thierry of Alsace) had favoured the French king (Louis VII) but he then leaned towards Henry, as the wool trade between England and Flanders (passing through the port at Boulogne) was very profitable to both parties. Relations between these two trading partners became so friendly that when in 1157 Thierry went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem he appointed Henry as the guardian of his eldest son, Philip.

Boulogne and a forced marriage

In 1159 William of Blois, the second son of King Stephen, fell ill and died outside the gates of Toulouse, presumably when he was part of Henry II’s army. This left vacant the lordships of Mortain and Boulogne; the latter included manors in Colchester and London. Henry added Count of Mortain to his long list of titles but wanted to grant Boulogne to Thierry’s son, Matthew. However, William’s sister, Mary, inherited the county and became Countess of Boulogne. Around the year 1150 Mary became a nun and by 1155 she was Abbess of Romney Abbey in Hampshire.

This could have scuppered Henry’s plans in regard to Boulogne but he soon managed to find a way to settle matters to his satisfaction. On Henry’s order Matthew abducted Mary from Romney Abbey and forced her to marry him. This raised up Matthew to be co-ruler of the County of Boulogne and thereafter he was favourable towards England. The marriage between Matthew and Mary was annulled in 1170 and she then became a nun at Montreuil, dying there in July of 1182.

Toulouse

In 1163 a treaty originally set up during the reign of Henry I was renewed between Henry II and Thierry of Alsace, through which Flanders would provide Henry with knights in exchange for an annual payment.

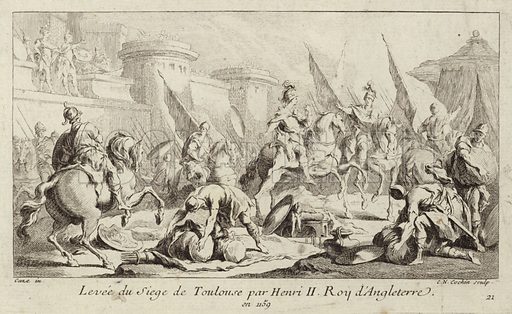

Henry’s first major campaign on the Continent was against Toulouse, which he claimed should be his by right through his wife’s inheritance. The county was the largest in the kingdom of France and the city of Toulouse was very rich and heavily fortified. Other significant cities included Narbonne, Cahors, Nimes and Carcassonne.

By Charles Nicholas Cochin II (1715-90)

In June of 1159 Henry assembled a large army (one account says the army was led by his Chancellor, Thomas Becket), with contingents from his territories in France, plus English soldiers and added forces from Flanders and Scotland. There can be no doubt that these fighting men hoped to be able to share out the wealth of Toulouse between them. Henry attacked from the north, whilst some of his other supporters opened fronts in different areas.

Cahors was captured together with a number of other castles and the fighting dragged on after Henry left to sort out problems elsewhere in his empire. He was in Toulouse again in 1161 but then left it to his allies to continue the struggle for the county. In 1173 the Count of Toulouse, Raymond V, finally gave up and paid homage to Henry II of England.

Brittany

In 1156 the Duchess of Brittany, Bertha, died. Bertha was the widow of Alan de Bretagne, with whom she had a son, Conan. On the death of his father in 1148 Conan had inherited the title of Earl of Richmond. When his mother died Conan became Duke of Brittany. In 1160 he married Henry’s cousin, Margaret of Scotland. There was a tradition of weak rule in Brittany and discontent amongst the nobles led to a revolt in 1166. This was put down by Henry, who then betrothed his son Geoffrey to the daughter of Conan, who was forced to abdicate in favour of his future son-in-law. This left Henry in control of Brittany, a situation to which many Breton nobles were opposed. This led to invasions of Brittany, which were followed by confiscations of estates of holders, who were replaced by supporters of Henry.

By 1173 Brittany, though not officially part of Henry’s empire, was under the control of men loyal to him. The way that Henry manipulated the affairs of Boulogne, Toulouse and Brittany highlights the method in which he gained influence over territory he did not have direct rule over.

Thomas Becket

Becket’s early life

Thomas Becket was born in 1119 or 1120 in Cheapside, London. Both of his parents were of Norman descent and his father owned property in London. He was influenced by Richer de L’Aigle and visited his estates in Sussex. Becket was fortunate enough to receive a good education but was forced to take up a position as a clerk when his father’s business interests suffered a setback. Later on he gained a position in the household of Theobald, Archbishop of Canterbury. He represented Theobald on missions to Rome and was then sent to study canon law at Bologna and Auxerre. In 1154 Theobald raised Becket up to Archdeacon of Canterbury and gave him several other ecclesiastical offices.

Beckett and Henry become close friends

He proved to be so efficient that in January of 1155 Henry II appointed him Lord Chancellor of England. Becket and the king soon became close friends. From relatively low beginnings, Becket had risen up to be the holder a secular position second only to the king. It is said that he became famous for his luxurious style of living and that his table was resplendent with gold and silver plate.

Archbishop of Canterbury

Theobald died in 1161 and the See of Canterbury was vacant for more than a year. Early in 1162 Becket was nominated as Archbishop of Canterbury and on 23 May his election was confirmed. Many said he was undeserving of this high ecclesiastical office, for his lifestyle was too extravagant and worldly. No doubt King Henry believed he would be the ideal archbishop, as he would put the government of the realm before that of the Church.

On 3 June 1162 Becket was consecrated as Archbishop of Canterbury by Henry of Blois (brother of King Stephen), Bishop of Winchester, together with other subordinate bishops. The king was in for a great surprise, for the consecration of Becket turned him into a different man. He took his position as head of the English Church extremely seriously, even when it meant antagonising the king. Their close friendship was soon forgotten.

Disputes

One of their disputes centred on the way that churchmen who had committed crimes could circumvent the civil law by being tried in an ecclesiastical court. In this way their punishments, if any, were usually far less severe. Henry demanded that miscreant churchmen should be defrocked and handed over to the civil authorities. This was opposed by Becket and in this he received support from other high officials of the Church.

In January of 1164 Henry drew together a council at Clarendon and presented the bishops with a statement of the king’s customary rights over the church; he then demanded from them a promise to observe these customs. After arguing for two days Becket gave in. However, he then changed his mind. Thoroughly exasperated by this, Henry summoned him before the Royal Court to answer trumped-up charges. Becket was found guilty and stripped of all his estates.

Fleeing to France and returning to England

In fear for his life, he fled from England and appealed to Louis VII of France and the Pope for protection. However, by first agreeing to the demands made at Clarendon and then doing an about-turn, he left the English Church in a state of confusion.

From La vie de Seint Thomas de Cantorbéry by Matthew Paris, 1220 – 1240

In 1169 Henry met Becket (perhaps by appointment) at Touraine in France and this led to the archbishop being recalled to England.

His return on 2 December 1170, amidst a splendid retinue, is said to have been welcomed with great applause.

The final straw

On 14 June 1170 Henry II had his eldest son crowned by the Archbishop of York as King Henry III. This is the first and only time that there have been two kings of England at the same time.

From La vie de Seint Thomas de Cantorbéry by Matthew Paris, 1220 – 1240

After spending years in exile Henry might have hoped that Becket would be more conciliatory in his dealings with the king. This wasn’t to be. Becket was furious that the Archbishop of York had taken part in the coronation on 14 June and he persuaded the Pope to suspend the archbishop.

It was in a rage after hearing about this that Henry II uttered the words: “Will no-one rid me of this turbulent priest?”

Murder

Photo: Jeff Buck CC By SA2.0

On 29 December four knights (William de Tracy, Reginad FitzUrse, Hugh de Morville and Richard le Bret) entered Canterbury Cathedral and murdered Thomas Becket. Afterwards they took all the loot they could lay their hands on and then rode off.

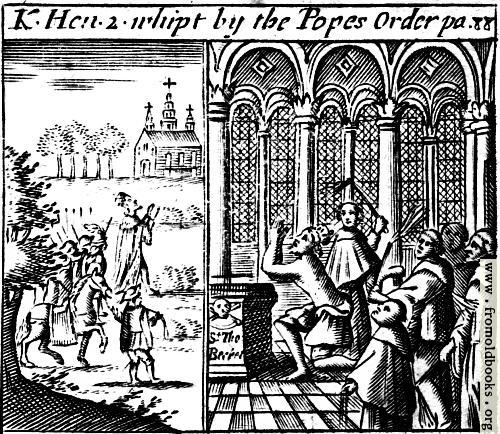

This deed shocked the entire Christian world. Henry II did penance for this crime and in record time Pope Alexander III declared Becket to be a saint.

From Wonderful Prodigies of Judgement and Mercy, by Robert Burton, 1685

The coinage

It is probable that the last issue of pennies of Stephen (‘Awbridge’, type 7) started to be struck after the king had agreed that Henry would succeed him on the throne of England. They would continue to be struck until 1158, when the first coinage commenced in the name of Henry II. The new king had much work to do at the start of his reign, so the currency of the realm would be left to others.

In 1154 all sorts of official and unofficial coins would be in circulation. The latter would include many baronial coins, which were struck without royal authority under the slack rule of Stephen. In 1158 a new coinage (from 31 mints) commenced: the obverse with a crude portrait of the king and the reverse with crosslets in the angles of a cross pattee.

Tealby coinage

A large hoard of these coins was found at Tealby in Lincolnshire in 1807 and afterwards pennies of this type were named after that hoard.

The weight and fineness of English pennies remained the same. However, the standard of striking of the ‘Tealby’ type was appalling as illustrated here by one of our reader’s finds.

Well-struck specimens are few and far between.

Found by Anthony Hopkinson

The only exceptions being some of those from the northern mints situated in Carlisle, Durham and Newcastle, as illustrated by this find from Anthony Hopkinson.

Improvement to the coinage

In 1180 the ‘Tealby’ coinage came to an end and was replaced by coins with a voided short cross with a cross pommee in each angle on the reverse. This was a change for the better, for the standard of striking was far superior to pre-1180 coins. For this coinage the number of mints was reduced to only ten; they were spread about the country to facilitate the circulation of coins. Below are examples of this coinage found by readers of this website:

Rhuddlan

From around 1180 until well into the reign of John, there was a mint at Rhuddlan in Wales.

The dies were produced locally and the coins struck from them do not conform to the rest of the short cross series. The example shown here was found by reader, John Lashmar.

Anglo-Gallic coins

The reign of Henry II witnessed the first issue of Anglo-Gallic coins. These would come to be struck not only in the king’s name but also in the names of other members of the royal family. Over time the Anglo-Gallic coinage became larger, more complicated and included gold, silver and base metal issues. The earliest coins (the denominations were deniers and oboles) were struck in the name of Henry II to circulate in Aquitaine. Although meant only to circulate in parts of France, a few Anglo-Gallic coins ended up in England and occasionally turn up as detecting finds. The early coins and some of the later ones are not scarce but the series includes some extreme rarities, which are eagerly sought after by collectors.

Henry II and the laws of England

Curia Regis

During the reign of Henry II there was no House of Commons. There were laws of one kind or another, which the king would swear to uphold at the time of his coronation. The Curia Regis (Court of the King) was the central court, which the king, as supreme feudal lord, held for his tenants-in-chief (both secular and spiritual) and this could be described as a House of Lords. Others who had some kind of special knowledge or influence might also be called to attend the Curia Regis.

Development of the justice system

Henry saw a need to spread royal justice over all his subjects. It has been said of him that one of his greatest achievements was his development of English government and justice. His measures included giving the Curia Regis the exclusive jurisdiction over all serious crime; the establishment of the principal of the ‘King’s Peace’, which meant that a crime was no longer regarded as a wrong against an individual but instead as a wrong against the State. He hastened the demise of the old and unsatisfactory means of trial (ordeal and battle) by developing the system of trial by jury. All this tended to make the English more equal with their rulers. In 1154 lectures on canon and civil started to be held at Oxford.

Feudal system

Amendments were also made to the feudal system, one of which led to an increase in the payments of scutage. The feudal system was based upon reciprocity. At the top end a tenant-in-chief had been granted land in exchange for specific obligations, the main of which was to provide the king with fully equipped fighting men during times of need. The tenants-in-chief themselves could grant land to lesser tenants, who also had obligations, which could include military service. At the bottom end of the feudal triangle were serfs, who were tied to the estate they lived on. They would have to do a specified amount of unpaid work and in return they would be under the protection of whoever ruled over the area in which they worked.

Scutage

The payment of scutage released a person or institution (for example a monastery or abbey) from a certain obligation. Henry was a very wise man and must have speedily realised that when people are paid they will put in more effort than if they are doing something simply because they are obligated to do it under the feudal system. Therefore, when he was in need of an army he often called upon his tenants-in-chief not to provide men and arms but to pay scutage instead. Leading on from this, whilst part of an army might have joined through being obligated to do so, the other part would be there because they were being paid.

Money

The money in circulation greatly increased when the voided short cross coinage was introduced in 1180. Whole pennies become more common, as do cut fractions. This may well be to do with scutage descending down the feudal triangle. Tenants-in-chief and their sub-tenants may have been in the same mind as King Henry, in that they had come to believe that men worked harder and longer for cash. Therefore, even some of the lowest members of society may have been able to pay scutage in order to release them from obligations owing to their immediate superiors.

Family affairs

When there was trouble somewhere within or outside his empire Henry was willing to take up arms when he was challenged. Experience would have taught him that it was impossible to keep everyone content but the challenges of the early 1170s came from an unexpected source: his own family.

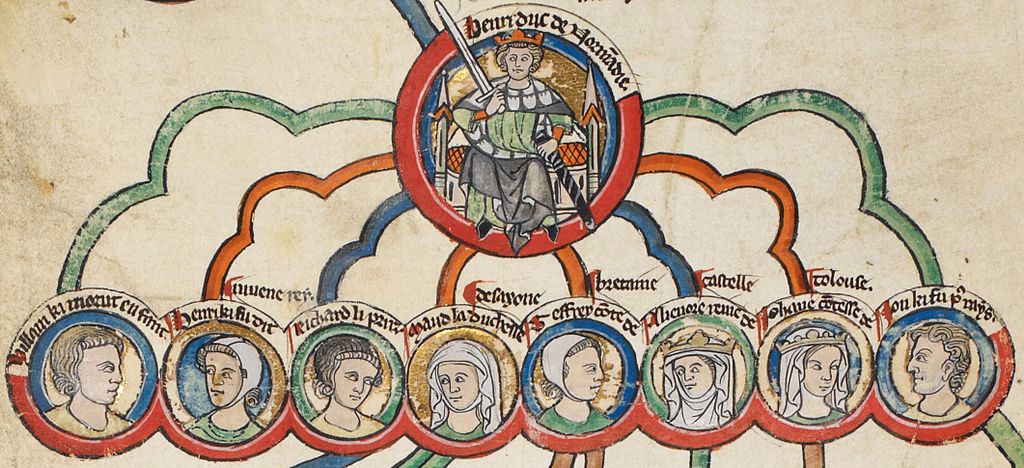

From a Genealogical Roll of the Kings of England,14th century.

The disputes would involve his four surviving sons: Henry, Richard, Geoffrey and John.

Young Henry

In 1170 Henry’s oldest surviving son, Henry, had been crowned as king but was given no land to support his raised status. A couple of years later Richard became Duke of Aquitaine. In 1173 the Young King Henry asked his father if he would grant him part of his inheritance – England, Normandy or Anjou – but Henry refused.

The Young King was so upset by this refusal that he joined Louis VII at the French Court. The younger Henry then joined with Eleanor (his mother) and together with his brothers Richard and Geoffrey revolted against Henry II. Seizing on an opportunity to bring down Henry II, William of Scotland, Count Philip of Flanders, Count Matthew of Boulogne and Count Theobald of Blois joined with them. King Henry put down the revolt and imprisoned his mother.

Photo: Rene Boulay, CC BY-SA 3.0

William of Scotland was captured and held at the Chateau de Falaise in Normandy where he was forced to sign the treaty of Falaise.

Hugh Bigod again

In England one of the main leaders of this revolt was an old enemy of the king, Hugh Bigod. Together with Robert de Beaumont (Earl of Leicester), he besieged and took Hagenet Castle in Suffolk. However, Robert was taken prisoner at the Battle of Fornham (near Bury St. Edmunds) by Richard de Luci and other barons. Robert then turned against Hugh, who was forced to enter into negotiations. The end result was that he had to surrender his castles but he was allowed to keep his land and earldom. Hugh would never again have the strength or will to trouble King Henry II.

Richard and then John

Louis VII died in 1180 and was succeeded by his son, Philip, who was 15 years old at the time. Henry’s fourth son, Geoffrey, became Duke of Brittany in 1183. Richard’s administration of Aquitaine made him unpopular and in 1183 the younger Henry joined in a revolt to overthrow him. Others involved were Philip of France, Count Raymond V of Toulouse and Hugh III of Burgundy. However, the death of Henry later in 1183 led to Richard holding on to Aquitaine.

The death of the young Henry left Richard as heir apparent to Henry II. Richard refused when he was ordered by Henry to hand over Aquitaine to John. Geoffrey of Brittany fell out with his brother Richard and Philip II hoped to use this to his advantage. However, this plan came to nothing when in 1186 Geoffrey was killed whilst taking part in a tournament.

Soon after this Philip and Richard became allies. Needless to say, this was much to the displeasure of King Henry. In 1188, after paying homage to Philip II for the Continental lands held by his father, Richard and Philip went to war against Henry II. Le Mans, Henry’s place of birth, was captured, Tours fell, and Henry was eventually forced to surrender at Chinon.

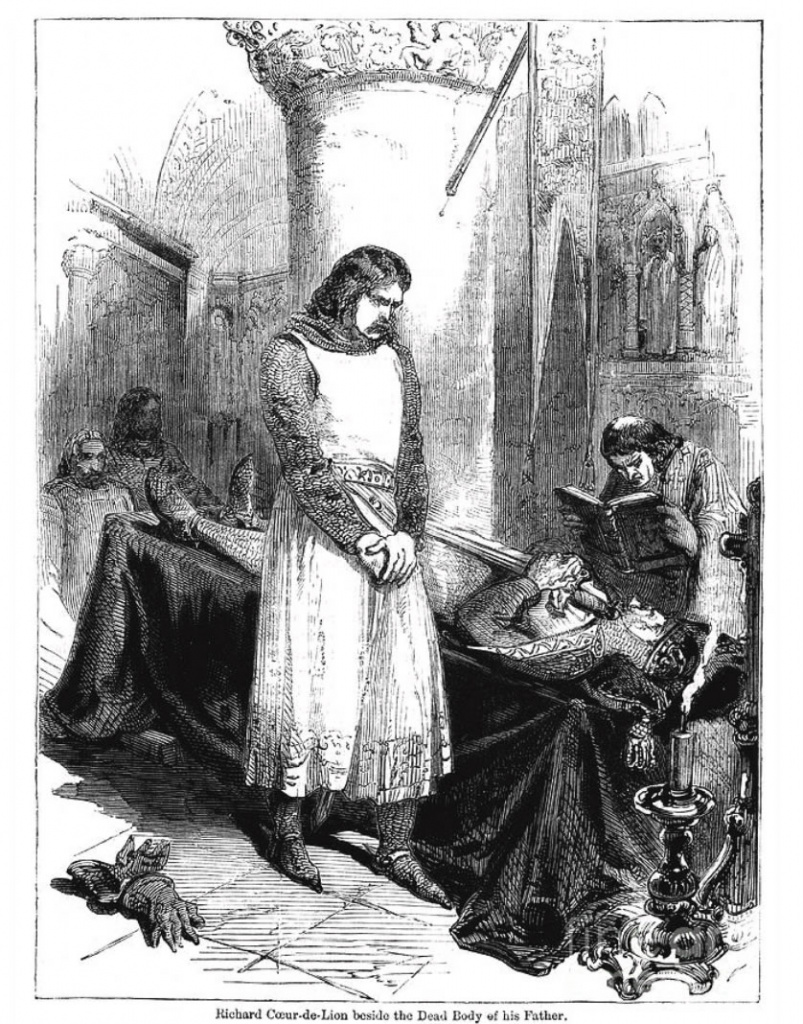

From Cassell’s Illustrated History of England, 1890

Two days later Henry died, some say of a broken heart, after hearing that John, the son who had previously stayed loyal to him, had joined with Philip and Richard.

Henry II’s legacy

Brighter future after the civil war

In 1154 Henry became king of a country whose people had lived through a civil war fought between King Stephen and supporters of the Empress Matilda. Some of the ruling elite might have profited from this but most ordinary folk must have been relieved when the conflict ended, for it allowed them to get on with their everyday lives. Thus, the death of Stephen would have brought a sigh of relief and the crowning of Henry II will have met with cheering and hopes for a brighter future.

Control over the law and finances

With England free from strife Henry could attend to other matters of State. His legislative achievements, merely touched on in this article, were many. The strict control over the Exchequer ensured that money wasn’t wasted or misappropriated by those appointed to collect it. And, all the tenants-in-chief in England bowed to the word and authority of the first king of the Plantagenet dynasty.

Energetic and cunning

Louis VII of France once commented that the King of England seemed to be here, there and everywhere all at the same time. This, of course, would be impossible but when inspecting parts of his empire he did it with great speed. Fortunately for him, he started his reign as a young and fit man, so he would take in his stride the distances covered. Henry had boundless energy, a sharp and educated mind, imagination and vision. However, when the situation demanded it he could be forceful, cunning and manipulative, which, it could be argued, were attributes needed by a 12th century ruler of both England and lands on the Continent.

Four great lessons

It has been said of Henry II that by the time of his death four great lessons had been instilled into the English people:

One: They had been taught to pay taxes, which is a lesson the French monarchy never succeeded in pressing home;

Two: They had been taught that a crime was an offence against the king’s peace, over which the Curia Regis would have exclusive authority

Three: They had learned that there was one law for whole country, administered by one supreme court, the Curia Regis, with its judges going on circuits throughout the country representing the power of the king; and

Four: they had become aware of the duty of co-operating in various ways in the task of government, either as tenants or citizens, or as jurors for the assessment of taxes, or in the judgement of cases in the county courts.

Over worked

Photo: Mark Cartwright CC A-NC SA

Rather than from a broken heart, the death of Henry II is more likely to have been caused by decades of over-work. All the years of strain and effort involved with governing a complex empire had finally taken their toll.