King Stephen – his life and coinage

The story of the life and times of King Stephen and the coinage produced during his reign.

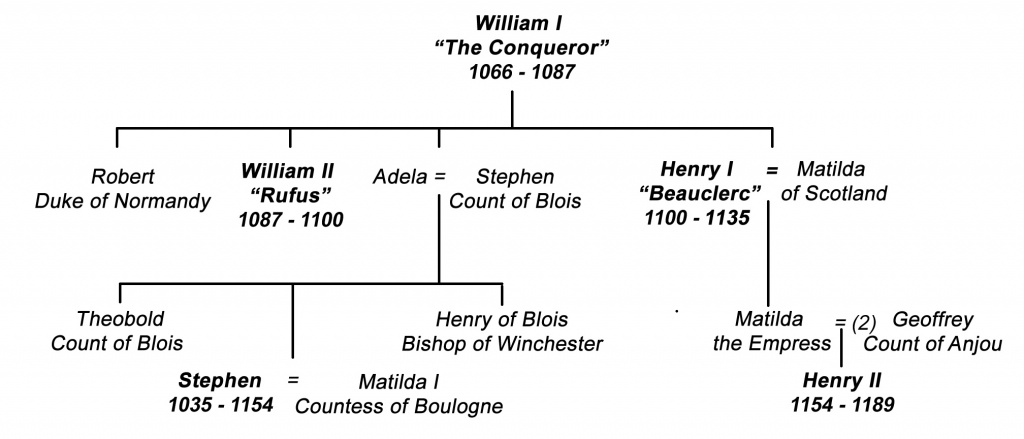

Stephen becomes king

At the start of December 1135, after a reign of 35 years, King Henry I of England died. In 1127 the leading magnates had all sworn to accept Henry’s daughter, Matilda, as Queen of England when Henry died.

However, in December of 1135 the same magnates must have been having second thoughts. Prior experience had shown that both England and Normandy needed a strong ruler; one who could call upon the support of the all the barons. Did Matilda have the necessary requirements? These doubts and other outstanding questions were speedily settled when Stephen of Blois (nephew and favourite of Henry I), acting with great speed, crossed the Channel and was crowned as king on 22 December 1135.

For a time Stephen’s brother hoped to become Duke of Normandy, which would have raised immediately a situation of divided loyalties. Therefore, most of the Norman barons pledged allegiance to Stephen as King of England and Duke of Normandy. Empress Matilda, widow of Henry V of Germany, was now married to Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou. As could be expected she was not at all happy that Stephen had usurped the throne of England.

The two Matildas

Queen Matilda, Countess of Boulogne

In 1125 Stephen had married Matilda, who was the daughter of and heiress to Eustace, Count of Boulogne. She was the granddaughter of Margaret of Scotland and great, great, great niece of Edward the Confessor, so had Scottish and Anglo-Saxon royal blood in her veins.

Matilda of Boulogne was popular and was tireless in her support for her husband. It was she who organised the events that led to Stephen’s release after his capture at Lincoln. When she died in 1151 Stephen is said to have been heartbroken.

Empress Matilda

The other Matilda was the daughter of Henry I and was known as Empress Matilda (or Empress Maude).

She seems not to have been popular; had she been conciliatory rather than haughty then events might have taken a different course.

War and conflict

King Stephen v King David of Scotland

King David invades

The first problem Stephen had to face did not come from Empress Matilda but from King David of Scotland. In January of 1136 the Scots invaded the north of England. The main reason for this was supposed to be to give support to Matilda’s claim to the throne. However, David might also have seen an opportunity to grab land before the new king had time to consolidate his position, as the Scots had a longstanding claim to Cumbria. Besides being King of Scotland, through his marriage to the daughter of the Earl of Northumberland, David was already and English baron. He had spent much of his youth at the Court of Henry I, where he was influenced by Norman ways and ideas.

Carlisle mint captured

Carlisle and its mint were swiftly captured and this led to the very first Scottish coins being struck. They initially copied the design of the last issue of Henry I but bore David’s name; slightly later coins would copy Stephen’s cross moline (‘Watford’) type.

King Stephen wins Battle of the Stamdard

In February of 1136 the English and Scots came to an agreement, through which the Scots were allowed to hold most of the territory they hade gained and David’s son, Prince Henry, became Earl of Huntingdon. Armed conflict was avoided by this settlement and in 1137 Stephen felt secure enough to cross the Channel to Normandy and enforce his rule on the duchy.

Watercolour by Sir John Gilbert, 1880

Relations between the English and Scots soon deteriorated and on 22 August 1138 two armies came together in a battle fought at Northallerton, which became known as the Battle of the Standard.

The English were victorious but David I and Prince Henry managed to escape. At this time it was becoming ever more likely that Matilda would be landing in England to pursue her claim to the throne. Being fully aware of this, after the battle Stephen granted the Scots very favourable terms. Rather than losing land, the Scots gained even more when Prince Henry was made Earl of Northumberland. Stephen probably hoped this would placate the Scots and deter them from offering support to Matilda if she arrived in England.

King Stephen v Empress Matilda

It must have seemed to Stephen that as soon as one enemy was pacified he had to contend with another.

Matilda lands in England

Geoffrey of Anjou had already invaded Normandy, so armed men were needed there to protect the duchy. As if this wasn’t enough, Matilda and Robert of Gloucester (an illegitimate son of Henry I) landed at Arundel on the south coast of England, together with 140 knights. Matilda stayed in Arundel Castle but Robert sped off to the West Country to raise more support. This was the start of the period that became know as the anarchy. Every part of England wasn’t involved and armed conflict was sporadic rather than continuous. However, many ordinary folk must have yearned for peace.

Stephen allows Matilda to leave Arundel castle

Illustration by James William Edmund Doyle, 1864

Stephen besieged Arundel Castle, so Matilda was trapped inside. Curiously, Stephen agreed to a truce, through which Matilda and her household knights were let out and escorted to the south west of England, where she met-up again with Robert.

King Stephen defeated and captured

By 1141 Matilda had the support of the Earls of Gloucester and Chester and of Henry of Blois (Bishop of Winchester and Stephen’s brother).

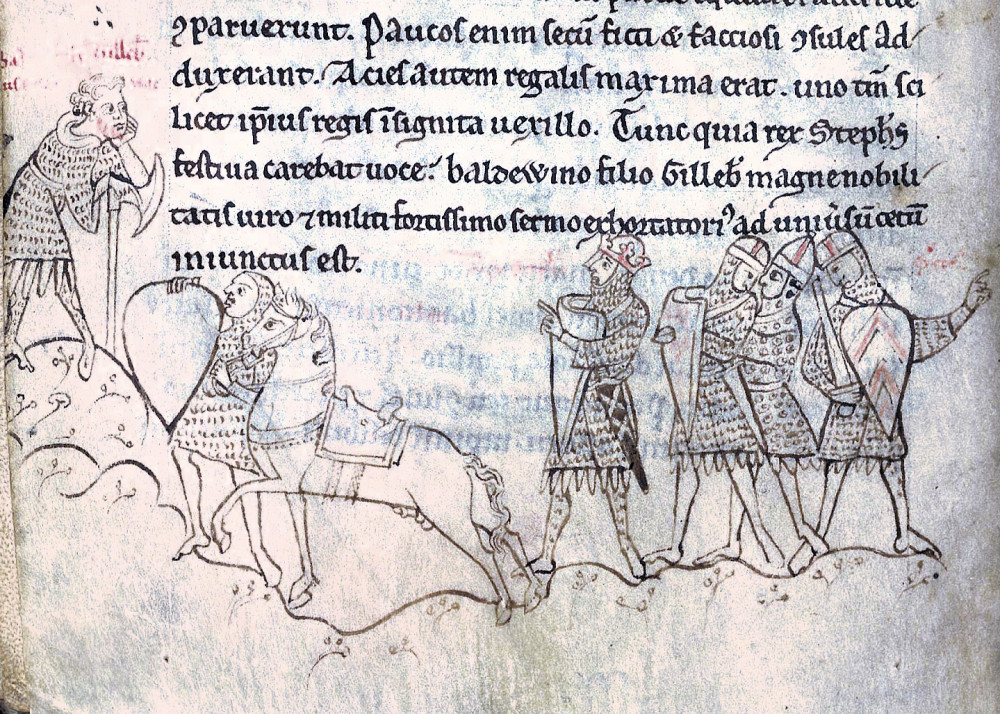

Henry of Huntingdon’s Historia Anglorum, c1200

On 2 February Stephen was defeated in battle and taken prisoner at Lincoln.

For a few months it looked as if Matilda had won. At a council held at Winchester, Bishop Henry said it was the clergy’s prerogative to choose and consecrate a king (or queen). The following day a delegation from London arrived. Instead of agreeing with Bishop Henry they said that King Stephen should be released.

Matilda loses chance of victory

Empress Matilda is then said to have proceeded to London, where she showed her most arrogant face and promptly levied a tax on the city. Not content with upsetting the Londoners, she then quarrelled with the Bishop of Winchester and was expelled from the city. Matilda was determined to take hold of the bishop, so with the aid of Robert of Gloucester and a small army she laid siege to the bishop’s palace, Wolvesey Castle.

Queen Matilda, Stephen’s wife, arrived with a much larger army and surrounded the besiegers. Earl Robert planned to break out and get his half-sister to the safety of Bristol, which was in the hands of her supporters; she managed to escape but Robert was captured. This was a loss that was too great to suffer; there was no other option open but to exchange him for Stephen. With the king free again to organise the war, Matilda’s chance of victory was gone. However, she still possessed enough support to prevent Stephen from gaining total victory.

Matilda retreats to the West Country

The events of 1141 left Matilda in control of the West Country and Oxford, which covered the approaches to Bristol and Gloucester – her main headquarters.

In the winter of 1142 a plan was put together by Stephen to take Oxford with Matilda in it. However, she slipped out with only three knights accompanying her and eventually reached the safety of the West Country.

Count Geoffrey was proclaimed Duke of Normandy

In 1144 Rouen fell and Count Geoffrey was proclaimed Duke of Normandy. Now the leading barons in England who also had land in Normandy were faced with a quandary: who should they support? If they continued to uphold the right of Stephen to be king then their estates across the Channel might be confiscated. If they recognised Geoffrey as Duke then they might loose their English estates. No doubt when the question was asked of them their answer would depend on where they were at the time: in England or in Normandy.

Law and order

Never before 1066 did England have a unified government, nor was there a central court. The local courts of the shire and hundreds were supreme. The shire court was a kind of local Parliament, in that it fulfilled all three functions of government: judicial, executive and legislative. Its officials were the earl, bishop, sheriff and owners of pieces of land – through which they were bound to attend and act as judges at the shire court. The Norman kings saw in the sheriff a useful link between the local administration and themselves and made use of them as royal representatives. However, the power of the sheriffs was sapped by the expanding authority of the Curia Regis (Court of the King).

The Norman idea of government was based upon feudalism. The Anglo-Saxon Witan was little more than a group of great men whose advice the king chose to seek. The Curia Regis was different, in that it was made up of some men summoned by the king but chiefly of those who owed compulsory membership of it by virtue of the fact that the king had made grants of land to them on the understanding that they would perform for him services of various kinds. For example, they might have to provide a certain number of armed men.

The tenants-in-chief (largest landowners) could in turn grant land to lesser tenants, who would have to provide service of one kind or another to their lord. There was a major difference between English and European feudalism. In Europe a man owed allegiance to his immediate superior. However, in England all tenants, no matter what their status, owed allegiance to the king.

Geoffrey de Mandeville

During the period of anarchy the country lacked the strength and authority of a central government. Therefore, some barons did much as they pleased and it was not unusual for them to change sides more than once. Geoffrey de Mandeville is a good example of a turncoat. He initially sided with Stephen, who made him Earl of Essex in 1140. After Stephen’s defeat at Lincoln, Geoffrey switched his allegiance to Matilda. She granted him land and appointed him sheriff of Essex, Hertfordshire, Middlesex and London.

However, when Stephen was released from captivity Geoffrey once more pledged allegiance to him. He led a private army of brigands and plundered the countryside at will. In 1143 he was arrested and threatened with execution, so he surrendered two of his castles and the custody of the Tower of London to Stephen. Soon after this Geoffrey rebelled again and used the Isle of Ely and Ramsey Abbey as bases. He met his end in 1144, as a result of being shot by an arrow during a skirmish.

Photo: Christine Matthews, CC By SA.20

Having already been excommunicated by the Church, the burial of his body at Walden Priory in Essex was denied. His retainers wrapped the body in lead and for some time hawked it round various religious establishments pleading for it to be accepted. Geoffrey was eventually given up to the Templar community in London and his body interred in the Temple Church.

Breakdown in law and order

In other areas, too, some of the barons took advantage of the breakdown in law and order. Few were as ruthless, grasping and untrustworthy as Geoffrey de Mandeville but an English monk, when writing of this period, said: “They greatly oppressed the wretched people by making them work at their castles [mostly built without the permission of the king], and when the castles were finished they filled them with devils and evil men. They then took those whom they suspected to have any goods, by night and by day, seizing both men and women, and they put them in prison for their gold and silver, and tortured them with pains unspeakable, for never were any martyrs tormented as these were.”

The coinage

Had Stephen gained the throne by right then his coinage would probably have been fairly straightforward. In actual fact he usurped the throne. This led to invasions, civil war and barons taking one side or the other.

King Stephen’s coinage

When King Stephen’s official coinage was first classified it was split into seven different types. However, only two (I and VII) were nation-wide issues; type II and VI were struck in eastern England areas under the control of Stephen; the other types (III, IV and V) were struck in small numbers and did not circulate widely. In the case of type I there are several regional varieties. There is also a series of pennies struck from defaced dies, which were once thought to date from the time when Stephen was excommunicated. However, this theory is now believed to be incorrect.

This type VII penny, minted in Ipswich, was a detecting find from Norfolk in May 2021. It was sold by Spink for £1,500.

Prince Henry of Scotland

At the start of a new reign dies need to be made for making coins. Silver has to be refined, sheets rolled or beaten out and discs cut from them. Then the coins themselves need to be struck and put into circulation. All this takes time and the work might not have been completed when the Scots captured Carlisle and its mint early in 1136. This could explain why the first Scottish pennies struck at Carlisle copied the design of the last type (XV) of Henry I rather than the first type of Stephen. On the obverse they have the name of King David. Later on pennies would be struck bearing the name of David’s son, Prince Henry.

This Prince Henry penny from Carlisle was sold by Spink for £5,200 in 2011.

Baronial Magnate issues

Only the king could authorise the striking of coinage. Despite this, during the anarchy some of the barons on both sides started to make their own coins. This might have been due to a shortage of currency in certain areas, or an exercise in making a profit, or just to advertise their name. Issues attributed to York include coins of Eustace Fitzjohn, Robert de Stuteville, William of Anmale (Earl of York) and Henry Murdac (Archbishop of York) – see my article on a reader’s coin The story of Henry Murdac – a penny of Stephen.

This penny of Robert de Stuteville was a detecting find from North Yorkshire in March 2020. It reads RODBERTVS D S|TV on the obverse. This remarkable issue has been the subject of numismatic debate for over three centuries. The auctioneer, Spink, have written a detailed analysis here.

Maltida’s issues

Coins were also struck at Cardiff, Bristol, Oxford, Wareham and other places in the name of Matilda. The names of her supporters found on coins include Brian Fitzcount, Robert and William of Gloucester, Henry de Neubourg and perhaps Patrick Earl of Salisbury, together with some pennies in the name of King William and King Henry, which may be meant to commemorate previous Norman kings.

This penny of William of Gloucester is thought to have been minted in Sherborne, Dorset. It’s a detecting find from 30 August 2020 at Stalbridge Weston, Dorset. It was recently sold by Spink for $13,000.

William was the son of Robert of Gloucester, who was exchanged for Stephen after the Battle of Winchester.

Numismatic legacy

For those living through the anarchy life must have been hard. For later numismatists the period has left a legacy of a fascinating range of official and unofficial coinage, some of which carry the names of well-known personalities of the period. New varieties continue to turn up and even new names, for a penny of Henry de Neubourg from the Swansea mint was not discovered until fairly recently. When these coins were struck they just represented cash to be spent or hoarded but today they help us to piece together the events of long ago. And, of course, they have turned into sought-after collectors’ pieces.

The final settlement

Stephen attempts to name his son as successor

In 1147 Robert of Gloucester died and in 1148 Matilda retired to Normandy, which by that time had been conquered by her husband, Geoffrey Plantagenet. With her departure the anarchy that had engulfed parts of the realm since 1139 subsided. This, though, did not mean the Stephen’s hold on the throne of England was not undisputed. Matilda’s eldest son, Henry, had first visited England in 1142 but soon returned to the security of his father’s dominions. By 1147 he was 14 years of age and felt confident enough to make his first attempt on the English throne. This failed, as did another in 1149 but when he returned to the Continent his father raised him up to be the Duke of Normandy early in 1150.

The marriage of the French king (Louis VII) to Eleanor of Aquitaine was annulled in 1152 on the grounds of consanguinity (too closely related). Very soon afterwards Eleanor married Henry, which brought him more land, wealth and power.

Stephen held on and tried to ensure the succession of his eldest son Eustace by having him crowned. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Theobald, was head of the English Church and loyal to Stephen but was more concerned for the unity and peace of the kingdom than for the military success of the king. The Church decided against the coronation of Eustace and in 1152 the Pope also forbade it.

Henry becomes king

Henry invaded England again in 1153, this time with a much larger army. A few months later Eustace died. This led to Archbishop Theobald and Bishop Henry of Winchester bringing together the barons who wished for peace. In November an agreement was reached, whereby Stephen would be king until his death (1154) and then his second son would inherit his land and Henry Plantagenet would gain his kingdom. This settlement brought an end to many years of conflict.

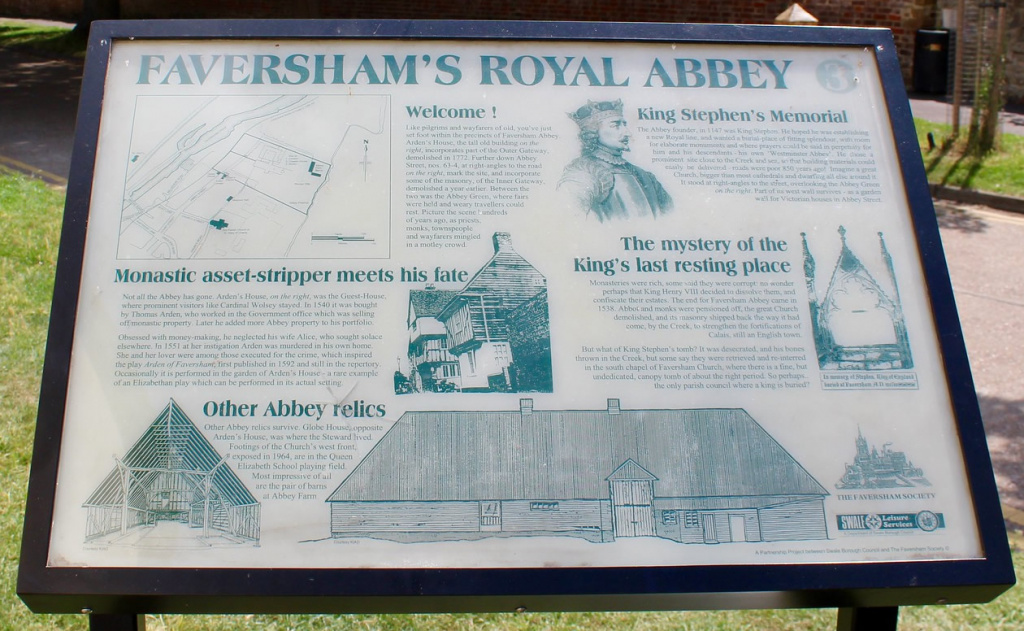

King Stephen buried at Faversham Abbey

Photo: John K Thorne CC By SA2.0

King Stephen was buried at Faversham Abbey, which he founded in 1148. Queen Matilda and their son, Eustace, were also buried there. Their bones were reportedly thrown into the nearby Faversham Creek when the abbey was demolished.

King Stephen, the last Norman king

Apart from Matilda and her supporters, few people at the time or later had a bad word to say about Stephen. He is variously described as being brave, gallant, capable, loyal and a competent baronial leader.

Stephen’s lack of ruthlessness

Stephen certainly lacked the ruthlessness that seemed to be bred into the first three Norman kings. A prime example is when Matilda was besieged in Arundel Castle. She was allowed to go free with a number of men who would later fight for her claim to the throne. It is highly doubtful that William I, William II or Henry I would have done the same thing. A more likely scenario is that Matilda would have been captured and her men put to death. Matilda herself might then have met with some kind of ‘accident’, by falling from the battlements of Arundel Castle, or being thrown from a horse onto stony ground. Perhaps Stephen released her through a sense of chivalry but if so he would live to regret it.

King Stephen’s inability to complete a task

Despite his numerous qualities, Stephen had difficulty both in controlling his friends and subduing his enemies. His problems in these two areas could have been due to those selfsame qualities. Yet again, the lack of a streak of ruthlessness might have been his main problem. Whilst he was unlikely to lose the war against Matilda, he was just as unlikely to ever be in a position to win it. Gervase of Canterbury said of him: “It was the king’s custom to start many endeavours with vigour, but to bring few to a praiseworthy end.”

William I to Stephen

On Christmas day of 1066 Duke William of Normandy was crowned King of England shortly after defeating Harold II in battle.

Illustration from Historia Anglorum, Matthew Paris, c1250

He was succeeded in 1087 by his second son, William, who was killed in 1100 by an arrow whilst hunting in the New Forest. The third son of the Conqueror, Henry, then took the throne and reigned until 1135. The next king was Henry’s nephew, Stephen, who grasped the throne, even though all the magnates had sworn that they would give allegiance to Matilda, the only surviving legitimate child of King Henry.

Anglo-Saxons and the Normans

As mentioned earlier on in this series, the Anglo-Saxons were a minority. Therefore, when Harold II was defeated in 1066 a minority ruling elite of Anglo-Saxons was replaced by another minority: the Normans. Did England gain or loose from this change?

Norman yoke

Historians refer occasionally to the ‘Norman yoke’. This notion first arose during the Civil Wars of the 1640s and again during the latter part of the 18th century. It looked upon the ruling elite of England as descendants of foreign usurpers, who had destroyed an Anglo-Saxon golden age. The main supporters of this view were those who wished for radical change in the power structure of England. It was a useful argument during times of unrest, especially during the 1640s and the troubled period near the end of the 18th century. Whilst it was true that some of those in high positions were of Norman descent, ordinary folk would have been no worse off and could even have been better off than they would have been had there never been a Norman Conquest in 1066.

Language

As a result of the Battle of Hastings, the Anglo-Saxon tongue was looked upon as the language of ignorant serfs. The clergy spoke Latin and the secular rulers spoke the Norman version of French. However, the ‘language of the ignorant’ would continue to adapt, develop and be refined and would eventually be used by great writers. The famous historian G. M. Trevelyan said: “It [the English language] is symbolic of the fate of the English race itself after Hastings, fallen to rise nobler, trodden under foot only to be trodden into shape.”

Another historian, Henry Ince, when summing up his view of the period from 1066 to 1154, wrote: “England without the Normans would have been mechanical, not artistic – brave, not chivalrous – the home of learning, not of thought – a state governed by its ecclesiastical power, instead of a state controlling the civil influence of its church. We owe to the Normans the builder and the statesman.” Therefore, to Ince the benefits gained through the Norman Conquest outweighed the disadvantages. Some might not agree with him but I’m of the same mind.

Thank you Peter, a good informative read, especially living in Box.