From Henry VII to a unique Charles I coin

Steve Smith recently sent in a couple of coins. He mentioned that it was his wife, Jill, who found this Scottish rarity a couple of years back. Many of those who look at this website probably missed my first write-up of Jill’s find. As it is a really special, I’ve decided to retell the story.

Is it a mule?

When it surfaced Jill was baffled by it. She said that the head on the obverse looked like James I but the date 1629 on the reverse related to Charles I. When Jill contacted me she asked if it could be a mule but, whatever the case, I was asked to give a full ID. Take a look at the illustrations and see if you recognise the coin. As first sight it doesn’t make sense but with a bit of lateral thinking everything falls into place.

Historical Background

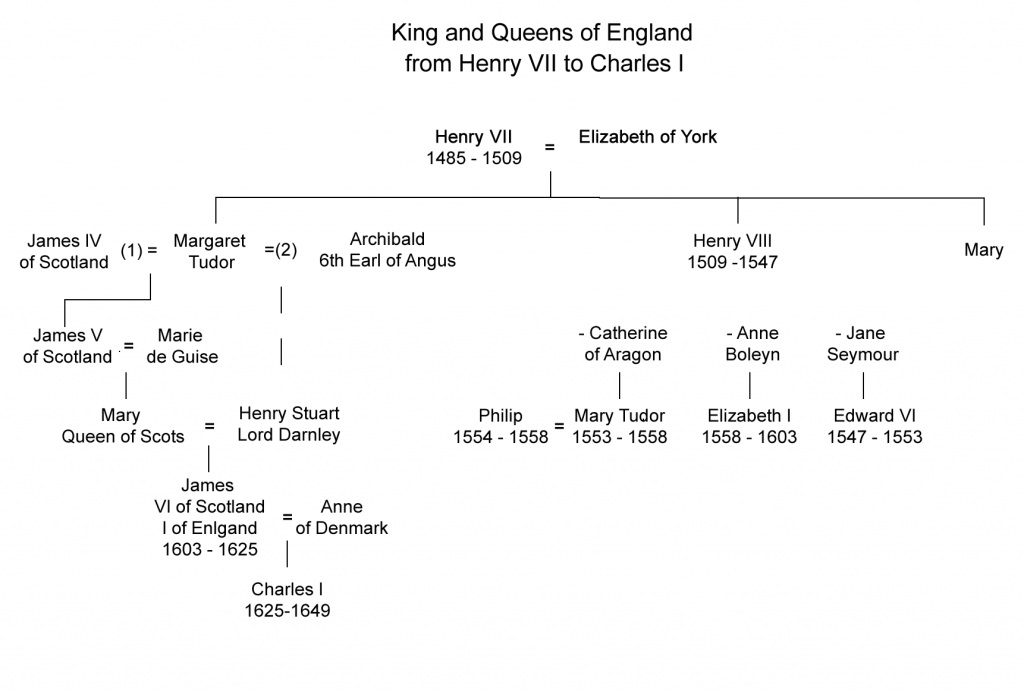

To explain why it came to be struck I have to go back to the reign of Henry VII.

Following the chain of marriages, births and events will lead to Charles I becoming king of England. This course of history will shape the design of Jill’s coin.

Henry VII

In 1485, at the Battle of Bosworth Field the last Plantagenet King of England, Richard III, was slain. This led to Henry Tudor being crowned as King Henry VII. It was hoped that the marriage of Henry and Elizabeth of York (daughter of Edward IV) would bring an end to the many years of fighting between Lancastrian and Yorkist factions. There were sporadic rebellions but with the support of leading magnates and through Henry’s skilful diplomacy he survived and England prospered under his rule.

Henry VII’s daughter marries James IV of Scotland

In 1503 Henry’s daughter, Margaret, married James IV of Scotland. This union would benefit both countries, as it should have meant that war between the Scots and the English would be less likely. It would also determine who was to be king of England 100 years later.

Henry VIII

However, the previous good relationship deteriorated when Henry VIII came to the throne in 1509. This led to a large Scots army invading Northumberland in 1513. At a battle fought at Flodden Field the Scots were defeated and James IV was killed.

James V of Scotland

This left the son of James and Margaret as King of Scotland when he was a little over one year old. A regent would rule for many years but in 1528 he took charge of Scotland as King James V. His first marriage, in 1537, was to Madeleine of France but on her early death he then married Mary of Guise. This union produced a daughter, who would eventually become Mary, Queen of Scots. James died in 1542 and was succeeded by Mary, who was only one week old.

Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary was brought up and educated in France. She married the Dauphin (Francois) and no doubt looked forward to a long reign over both Scotland and France. This wasn’t to be, for Francois II died shortly after becoming king in 1560. Mary returned to Scotland and in 1565 she married Lord Darnley (Henry Stuart), with whom she had a son who was Christened James. Darnley was murdered in 1567 and the following month Mary married Lord Bothwell (James Hepburn), who was widely believed to have been implicated in the killing of Darnley.

James VI of Scotland

After a battle fought at Carberry Hill in 1567, a force loyal to Lord Bothwell was defeated and Mary was forced to abdicate. Her son by Lord Darnley then became James VI of Scotland.

Elizabeth I

For a while Mary was held prisoner in Lockleven Castle. In May of 1568 she escaped and fled to England. This presented a great problem for Elizabeth I, for what was she to do with a woman who was not only a Catholic but had also been a queen? For the time being Mary was kept locked up and under close guard. Her presence in England led to the Northern Rebellion, during which the Earls of Northumberland and Westmoreland aimed to restore Catholicism and place Mary on the throne. The rebellion was put down and was followed by executions of the Earls and others.

In 1586 the Babington Plot came to light. Through this Mary Queen of Scots was implicated in a conspiracy to murder Elizabeth of England. After much heart-ache and indecision, Elizabeth eventually signed the death warrant and in 1587 Mary was executed.

During the Christmas celebrations of 1602 Elizabeth fell ill and may have known she had little time left. She would not name her successor but knew that Sir Robert Cecil was discretely planning for James VI of Scotland (a staunch Protestant) to take the throne of England.

James VI of Scotland becomes James I of England

Thus, on the death of Elizabeth I on 24 March 1603, James VI of Scotland became James I of England. The two crowns were united but the two countries remained separate until the Union of England and Scotland in 1707.

Had not James VI of Scotland been a direct descendant of a member of the Tudor dynasty then he would never have gained the throne of England. Through the marriage of the daughter of Henry VII (Margaret) to James IV of Scotland, 100 years before, and later marriages and births, James VI was related by blood to Elizabeth I of England. Therefore, he was perfectly acceptable as the next monarch on the death of Elizabeth.

Coinage of James VI

Scottish currency was by no means as stable as the English. Since the reign of Robert III (1390-1406) it had been subject to debasement and almost continual adjustments to its face value. By 1603 there had been eight different coinages during the reign of James VI. The silver content was close to that of England but an English shilling passed for twelve shillings in Scotland. Soon after James VI came to the throne of England his Scottish silver coins became very similar in design to their English counterparts but with face values twelve times higher.

Coinage of Charles I

When James I died in 1625, his son Charles became king. The earliest Scottish silver coins of Charles I copied the designs of those of his father. The twelve and six shilling pieces even have the same portrait. Later on, in1637-42, the famous French engraver Nicholas Briot made dies and set up machinery that made silver coins far superior to those in circulation in England.

Jill’s Coin

Scottish six shilling piece of Charles I

Even though the portrait on the obverse looks more like James VI (James I of England) the coin found by Jill is a Scottish six shilling piece of Charles I. It is basically in Fine condition but the obverse has been struck off centre and it has a small bend in the edge. The denomination is very rare indeed for Charles I (see number 5543 in Coins of Scotland, Ireland and the Islands). Therefore, a specimen would count as a really great detecting find.

Dated 1629 – the only known specimen

But there is something about Jill’s find that makes it especially important and outstanding. Six shilling pieces of Charles I are known for every date between 1625 and 1634 except one: 1629. If you haven’t already noticed the date on Jill’s coin then look now, for it is none other than 1629. It is the missing link between 1625-28 and 1630-34. Wow! What a find! At this moment in time this Scottish six shilling piece is the only known specimen dated 1629.

Check your collections

Detectorists should check out their collections, to see if they have any Scottish six shilling pieces of James I and VI or Charles I. They are very similar to English sixpences of the same reigns but are much rarer and therefore of much higher commercial value. If you have one or find a specimen in the future then do let me know.

Exciting times

Some detectorists believe so much material has been unearthed that find rates will now start to shrink. I’m not of the same opinion. Sites continue to throw up outstanding finds and there is much land as yet unsearched. We have had some spectacular hoards and singleton finds over very recent years and I’m sure these will continue to be located over many years to come. We are living through exciting times, with much to look back on and as much or more to look forward to.

Valuation

Coin Valuation Service

Have your coin or artefact valued using my free online coin valuation service