Henry I – his life and coinage

Henry becomes king

Death of William II

On 2 August 1100, William II was killed by an arrow whilst hunting in the New Forest. William and his elder brother, Duke Robert of Normandy, had agreed that the land, titles and wealth of whoever died first would be inherited by the survivor. Therefore, Duke Robert should have become King of England.

Henry seizes the throne

Coronation of Henry I, king of England from a 17th Century manuscript

The group with William II in the New Forest included his younger brother Henry, known as Beauclerc because of his superior education.

Henry acted with great speed and transported the royal treasure from Winchester to London. Three days after the death of William II, his brother Henry was crowned at Westminster by the Bishop of London as King Henry I of England.

There must have been high level support for Henry in England, for had there not been he could not have seized the throne with such ease.

Duke Robert of Normandy claim to the throne divides loyalties

At the time of Henry’s coronation Duke Robert of Normandy was returning from the First Crusade. When news reached him that King William II had died, he would look forward to being ruler of both England and Normandy. Quite naturally, he would be infuriated when he heard that his younger brother had grasped the throne.

The problem of divided loyalties arose once more. With Henry as King of England and Robert as Duke of Normandy who should the leading magnates support? All had land in both England and Normandy, so to whom should they pledge their loyalty? Conflict seemed inevitable, so swords would be sharpened and retainers told to ready themselves for battle. Henry had invited Anselm (still the Archbishop of Canterbury) to return to England, in the hope of bringing the Church onto his side.

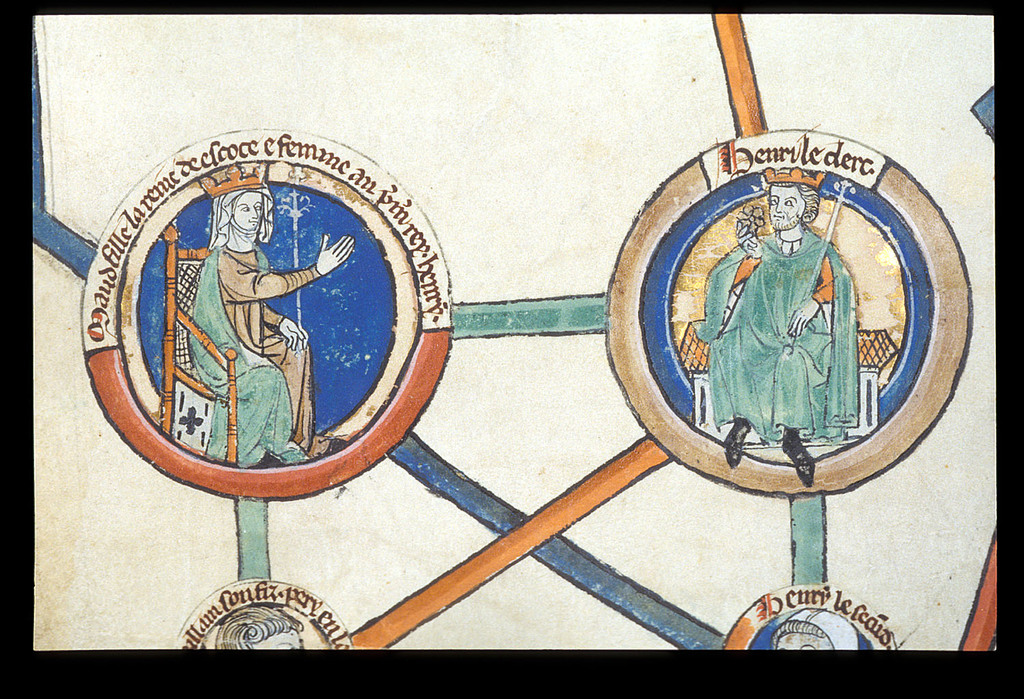

Henry marries Princess Matilda

14th Century illustration from Genealogical chronicle of the English Kings

In November of 1100 Henry married Princess Matilda, a descendant of Alfred the Great and daughter of King Malcolm III of Scotland.

The fact that Henry chose a Scottish rather than Continental wife was welcomed by ordinary folk in England. This union would not lead to support from the Scots but would at least ensure that the north would remain peaceful. Henry also managed to negotiate alliances with France and Flanders; neither wanted England and Normandy to be united under an over-mighty ruler, which could have happened had Robert become King of England.

Henry and Duke Robert clash

A second Norman invasion

On 20 July 1101, a fleet of 200 ships landed Duke Robert and an army of followers on the south coast of England. On hearing of this Henry feared not only for his kingdom but for his life. It is said that some of the leading magnates were preparing to desert Henry and go over to Robert. Others had yet to decide which of the two they would give their backing to. Archbishop Anselm was given the task of persuading the magnates to support Henry. He was successful, for few changed sides.

Settlement reached

Robert and Henry eventually met together and a settlement was worked out. Henry surrendered most of his land in Normandy and agreed to pay Robert a large pension of £2,000 per year; in return Robert agreed to recognise Henry as King of England. Thus, open warfare was avoided and Robert and his followers returned to Normandy. However, Henry distrusted some of the barons based in England, for he believed they would have given support to Robert. First and foremost amongst them was the rich and powerful Earl of Shrewsbury (Roger de Montgomery, father of Roger de Poitou), who had several strongholds in England. By the end of 1102 Henry he had stripped him of his land and power in England and the Earl departed to his estates in Normandy

Battle of Tiinchebrai

The settlement of 1101 did not last.

Henry’s supporters in Normandy were often harassed by Robert’s men and matters finally came to a head in 1106, when at Tinchebrai two armies came together in a short but vicious battle. Henry was victorious and Robert was captured, together with many of his chief adherents. Duke Robert was imprisoned for life (dying in captivity on 10 February 1134) and thereafter Henry ruled the duchy himself.

The battle at Tinchebrai was the most important since that fought near Hastings in 1066. Besides securing the position of Henry I, it is significant that a large proportion of those who fought for him were English. This was a true ‘coming together’, a unification of the conquered (in 1066) with the conquerors. William I thought of England as being a possession of Normandy; however, 40 years after 1066 it is likely that Henry I viewed Normandy as a possession of England.

After Tinchebrai Henry knew who he could rely on, for they had fought for him; he also knew the names of his enemies, for they had fought against him. In the months that followed several rebellious magnates were dispossessed and their land given to those loyal to King Henry. With a single person in control of England and Normandy the possibility of conflict between two different rulers could now be avoided. This situation was welcomed by both the king and the major landowners with estates in England and Normandy.

The honour of Eye

The honour of Eye, which was one of the largest landholdings in England, was granted to William Malet by William I. William Malet died in 1071 and the honour then passed to his son, Robert. Soon after the accession to the throne of William II, the new king dispossessed Robert Malet and granted the honour of Eye to Roger de Poitou.

During the reign of William II, Robert Malet was out of favour and spent much of the reign on his estates in Normandy. During this time or perhaps before, Robert became closely associated with Henry Beauclerc. He was in Normandy when William II was killed. He sped back to England and arrived in time for the coronation of Henry on 5 August. Robert became part of the inner circle of advisers to Henry I and held the new office of Master Chamberlain.

When Henry came to the throne Robert and Roger de Poitou would come face to face at the Royal Court. Quite obviously, there would be animosity between the two men; one had lost to the other a great estate in England. It was now Roger de Poitou’s turn to be dispossessed; the honour of Eye was taken from him and granted once more to Robert Malet.

In 1106 Robert died. It is probable that the honour of Eye then fell into the hands of the king. Henry held it for seven years and then granted it to Stephen, his nephew, who at the time was Count of Mortain. Stephen held it until 1135 and then gave it to William of Ypres, who was one of his most able military commanders. Yet again, this shows how the ownership of great estates and the revenue they produced could change hands quite frequently.

The coinage of Henry I

15 types of penny

As during previous reigns, the design of the silver penny was regularly changed. Between 1100 and 1135 there were 15 different types, mostly struck for very few years except the last type, which was issued over a period of ten years. The regular change in design allowed the king to gain a profit each time it happened. The sequence of types was first put forward in 1901 by W. J. Allen; in 1916 the order was changed by G. C. Brooke and over the years other amendments have been made. Coins are still catalogued according to the British Museum Catalogue numbers but the sequence now generally accepted is 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 7, 8, 11, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15.

Class I © DNW

Class IV © DNW

Class XIV

Three examples of a Henry I penny. The Class I and Class IV were sold by DNW in 2020 for £1,200 and £1,400 respectively. A reader sent in the other example. I valued this Class XIV penny at £800 in my article Henry I Penny.

Forgeriess and base metal coins

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, by 1124 “. . . the man who had a pound could not get a pennyworth at a market”. This was because many of the coins in circulation were thought to be forgeries or official coins struck in base metal. All the moneyers (about 150 at the time) were ordered to go to Winchester at Christmas. On the order sent by King Henry from Normandy, those found guilty of false coining were to lose their right hand and be castrated. Around 94 moneyers suffered this awful fate.

I have often wondered who carried out the punishment on the 94 men. It is highly doubtful that there would be an official hand-chopper and castrator, so the job would have been passed down. In overall charge might be a baron, who would tell one of his knights to do it; the knight would then pass it on to a retainer, who in turn would tell an underling to do it. At the end of the line would be someone at the lowest level. He who would be forced into performing a ghastly task 94 times, simply because he had no-one else to pass the job on to.

Were these men guilty of forgery and debasement? The evidence from hoards, present-day collections in private and institutional hands, together with a high number of finds, suggests that most (perhaps all) would be innocent. Many pennies of Henry I are badly struck and have little eye appeal. However, they are full weight, sterling silver and struck from official dies. “I’m innocent!” many of the moneyers must have cried. The poor man designated to mete out the sentence on them might have replied with: “So am I. But if I don’t do what I’ve been ordered to do then they’ll do the same to me.”

Halfpennies

Some round halfpennies were struck during the Anglo-Saxon period but examples are very rare. They were not struck during the Norman period until circa 1108, when halfpennies were issued by several different mints. The first wasn’t discovered until 1950, when it was published by Peter Seaby. However, more than one expert numismatist cast doubt on its authenticity. The coin was unique until 1989 when no less than five more specimens (all different mint and moneyer combinations) turned up. Today the number known will be around 25; all are different and almost all are detecting finds. There are so many different mint and moneyer combinations that the total number of round halfpennies struck could have run into several tens of thousands. They are still extremely rare but in 25 years’ time the number on record will be at least double today’s figure.

Henry I round halfpenny © DNW

This Henry I halfpenny was sold by DNW in April 2020 for £3,800. It is from Winchester mint and the moneyer is Godwine. The auctioneer says that there are four specimens known from Winchester, one each from the moneyers Ælfwine and Godwine and two by Wigmund.

Changes in coinage

Late in the reign of King Eadgar (959-75) a new coinage was introduced and became the model for all succeeding reigns. The obverse had a stylised portrait of the king and on the reverse was the name of the moneyer and the mint. However, the type was subject to regular change. The moneyers had to pay one mark (80 pence) annually for their office and one pound when the type was changed, plus a charge for each new pair of dies. Therefore, with the yearly fees and the charge for type changes, the king would reap a good annual profit from the coinage.

After the Norman Conquest, the weight and fineness remained the same. However, William I altered the moneyers’ annual payments to a single tax levied on every borough that had a mint. Savings’ hoards (as opposed to those containing coins of a single type) prove that not all the coins were exchanged when a new type was introduced. For some payments coins of only the current type could be used; therefore, persons who had accumulated savings would exchange only the amount of currency needed for these payments. When around 1125 the periodic change in type was abandoned this would have encouraged people to spend coins of any type. In doing so it might have led to a greater amount of cash being placed into circulation. This would have stimulated the economy, which in turn would have led to an increase in the amount of tax collected for the Exchequer.

Henry’s reign

War and conflict

William I and William II both had to contend with more than one rebellion. Henry I was more fortunate, for after Tinchebrai, apart from a few minor quarrels, England was free from conflict for the rest of his reign.

When a full scale war was being fought the king could raise an army through the feudal obligations of landowners – both secular and spiritual. Once the war was over the commanders, knights and foot soldiers would return to their bases in England or Normandy. However, besides his councillors and others there was a permanent military element in Henry’s Court. The latter has been described as “a professional corps of young knights”; they were well trained, extremely mobile and in Normandy were on a permanent war footing. These men garrisoned the many royal castles in the duchy. When the need arose they took part in battles, including the engagement fought against the French at Bremule in 1119.

If there was a need for more fighting men Henry hired mercenaries. However, this was only for a limited period during the early years of his reign. After Tincherbrai none were required in England and Henry had sufficient strength in Normandy not to need extra men. There can be no doubt that most of Henry’s subjects will have been delighted that peace rather than war prevailed for most of the reign. However, a contemporary chronicler wrote that professional soldiers (mercenaries), especially those from Flanders and Brittany, had “. . . hated King Henry’s peace because under it they had but a scanty livelihood”. These men would flock to England when war broke out during the reign of Stephen.

Law and punishment

I’ve already given an account of the way in which moneyers were punished because of the state of the coinage. Rather than being an isolated case, a sentence of mutilation was commonplace. Those found guilty of a crime could lose their nose, ears, tongue or eyes.

William I had abolished the death penalty, which could be interpreted as an early instance of compassion. Instead, it was because he preferred mutilation and less fatal forms of punishment. Henry I employed all the non-fatal penalties and was not averse to a sentence of death; in 1124 no less than 44 thieves were hanged in a single day.

Trial by combat and trial by ordeal were also used to settle cases. These were obviously useless in establishing guilt or innocence but both methods of trial would not fall out of favour until the reign of Henry II.

Government

The centre of government was the Curia Rigis, the Court of the King. This was made up of the tenants-in- chief (magnates holding land directly from the knig), together with the king’s personal servants and any others that King Henry believed could offer useful input; his servants and the ‘others’ helped to dilute the influence of the often over-mighty magnates. This was the beginnings of a civil administration body that would develop and grow over years to come.

In the counties the sheriffs were important officials of the Crown. The post of sheriff sometimes fell into the hands of powerful magnates but whenever possible King Henry appointed his own men to this post. Besides upholding law and order it was the sheriffs’ responsibility to collect taxes and fines owing to the king. This led to the creation of the Exchequer, whose name derives from the chequered boards used for calculating mathematical equations. Written records were kept on documents known as pipe rolls, so-called because they could be rolled up like a pipe; over the years some grew greatly in size.

Scotland

David I (1124-53) was the youngest son of Malcolm III and succeeded his brother, Alexander I.

David I of Scotland, stained glass window in Edinburgh cathedral.

Photo: Archdiocese of St Andrews & Edinburgh, CC BY-SA 4.0

In 1107 he received Cumbria and Lothian from his uncle King Edgar (who died shortly after the grants) and through his marriage he became Earl of Northumberland. David admired the Norman aristocracy and the feudal system they were attached to. He set about introducing feudalism into Scotland, in the hope that over time the authority of the clan chiefs would be undermined.

Normans were enticed into Scotland with offers of land and titles. One man who took up the offer was Robert de Brus; a descendant of this man would eventually become King Robert I of Scotland in 1306.

Religion

Henry I was more like his father, in that most of the time he respected the Church. Therefore, his mindset was totally different to William II, who was irreligious and viewed abbeys and churches are places to be plundered for his own profit. However, when Anselm died in 1109 Henry kept the see of Canterbury vacant for five years.

This was a time when reformers were pushing for changes of one kind or another in the Catholic Church. One contentious issue was in regard to the appointment of bishops and abbots. The Pope, seeking to limit secular control, wanted to be in charge of appointments. However, in England the highest ranks in religious establishments were great landowners; therefore, they had to swear loyalty to King Henry and this being so he argued that he should have the last word on appointments. Henry eventually renounced lay investiture but bishops and abbots still had to do homage for their landholdings. Arguments about whether the King of England or the Pope should appoint men to high offices of the Church would continue into other reigns.

Prince William

When Henry’s wife, Matilda, died in 1118 he had only one legitimate son – William. In 1119 William married the daughter of the Count of Anjou. In doing so this secured a useful political and military alliance.

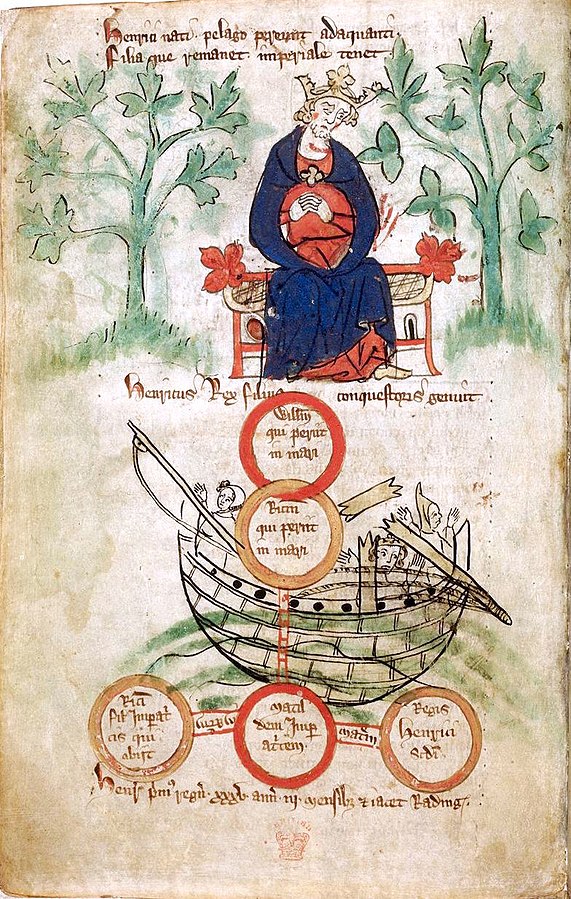

White Ship disaster

Tragedy struck in November of 1120, when a ship carrying William and other noble men and women was wrecked off the coast of France. There was only one survivor: a butcher, who had managed to cling to the mast until help arrived. Henry was devastated by this loss.

An illustration from c1321 showing Henry I and the sinking of the White Ship

This early 14th Century illustration depicts Henry and the sinking of the White Ship. In the red circle below Henry is written “Willelmum qui periit in mari” – William, who died at sea. In the red circle directly below the ship is “Matildam imperatricem” referring to Henry’s surviving legitimate child, Matilda.

He married Adelaide of Louvain three months later but their union was to remain childless.

Matilda

His daughter, Matilda, was married to Henry V, Emperor of Germany. In 1125 Henry V died but by then Matilda was well settled in Germany and would probably have lived out her life there. However, a daughter was useful for creating alliances, so Henry recalled her to England.

Matilda, from “History of England” by St. Albans monks, 15th Century

At a special gathering in 1127 of all the leading magnates they were made to swear that they would accept Matilda as Queen of England when Henry died. No doubt many of those present would have crossed their fingers when they swore the oath, as both England and Normandy might descend into chaos under the rule of a woman.

In 1128, much to her displeasure, Matilda was married off to the sixteen-year-old Geoffrey, Count of Anjou. This strengthened an alliance already in place. However, this worried many Norman barons, as it could eventually lead to England and Normandy being ruled by the Angevin who had married King Henry’s daughter. Geoffrey asked that some key Norman castles be given over to his custody but Henry refused. In the summer of 1135, after a period of peace and tranquillity, the two parties went to war. In December of the same year Henry I died.

Henry’s legacy

It could be argued that Henry should never have been king, for he had an elder brother with a better claim to the throne. If the death of William II was an accident, then Henry had been a very lucky man. He grasped the throne, successfully negotiated a compromise with his brother Robert, and then defeated and imprisoned him in 1106. A few ups and downs followed but Henry held England and Normandy together. He must have hoped that the same situation would continue under his daughter.

Henry had the attributes necessary for a strong king. He could be ruthless when the occasion called for it and generous to those who supported him. He was genuinely fond of his children, both legitimate and illegitimate – the most distinguished of the latter being Robert, Earl of Gloucester. Most contemporary chroniclers speak well of him but Henry of Huntingdon, after listing three gifts of ‘wisdom, victory and riches’ said they were offset three vices of ‘avarice, cruelty and lust’. William I and William II both accumulated a great deal of treasure. However, the difference between those two and Henry is that he managed to hold on to most of it.

The third Norman King of England died on 1 December 1135 and was buried at Reading Abbey, which he founded in 1121.

On hearing of the king’s death, the major landowners must have been restless at the thought of Matilda and her Angevin husband becoming the next rulers. Not for the first time, swords would be being sharpened and retainers told to be ready for action.