Have detectorists solved the mystery of Robin Hood?

By Paul Smith

Every once in a while I see a detecting find posted somewhere and it catches my imagination and I start to do a bit of digging to understand the background to the piece. Last week I saw a 14th Century seal matrix with the image of a hare riding a hound and thought what is that all about. That led me to do some research.

I found links to the first book on hunting in English, a famous district of London, the battle of Sedgefield, the Macclesfield Psalter and a stained glass window in Lincolnshire. Plus, there’s a connection with Lewis Carroll’s white rabbit, the famous pilgrim window at York Minster and St Anselm.

Putting all this together and with other similar detecting finds, I go on to ponder whether detectorists have finally solved the mystery of the identity of Robin Hood.

Hare riding a hound seal matrix

This seal matrix (“seal2”) was found in late summer last year in South Oxfordshire and was recorded at the PAS on 13 January 2022 as OXON-017218.

It depicts a hare riding a hound while blowing a horn. The encircling legend reads *SOhOV ROBIN. The seal is not uncommon, with at least 27 similar seals recorded on the PAS and many more elsewhere.

Hunting imagery proliferated in seal design and they were produced in vast quantities, particularly in the 14th century. They were most frequently not personalised by the use of a name in the legend and are known as banal or anonymous seals.

Existing Interpretation

The explanation given in the PAS records is that the hare riding a hound is that it is from “the world upside down” often seen in the marginalia of mediaeval manuscripts. In these, the normal roles are reversed. It is seen as wit and taking a dig at the aristocracy and their love of hunting.

The legend, SOHOV ROBIN, is interpreted as So Ho being a French hunting cry and Robin “probably” a generic name for a hound.

Legend and Imagery revisited

I will look at the three parts of this interpretation: SOHOV, ROBIN and the imagery.

SOHOV

There is strong evidence of “So Ho” being a hunting cry in the 14th Century from contemporary manuscripts and later from literature and place names.

The Master of Game

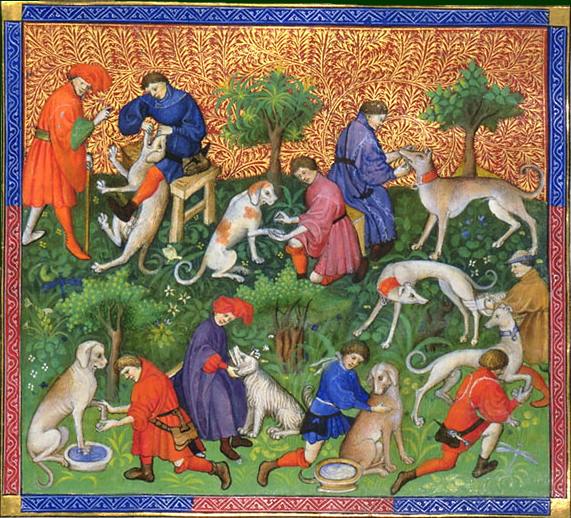

Illustration from Livre de Chasse, 1387-89

The Master of Game, written by Edward Langley, 2nd Duke of York between 1406 and 1413, is considered to be the oldest English language book on hunting1.

It is mostly a translation of Livre de Chasse written in French by Gaston Phoebus between 1387 and 1389. The illustration is from that manuscript, showing handlers tending to their dogs.

The hunting cries and language used in speaking to the hounds were still those brought into Britain by the Normans.2 Master of the Game details the calls to be given to the hounds. Several of these instructions would end in the words “so howe”. For example, if the hounds were on the wrong scent, the dog handler (or [ ]) would shout “Sto arere, so howe, so howe” , meaning “Hark back”. When the quarry was close enough for the faster greyhounds to be released the cry was “So howe, so howe, so howe”. The spelling changes in the book and sometimes it is “So Ho“

These instructions were almost exact copies of those in Gaston’s Livre de Chasse except “ta ho” was used instead of “so ho” . These are both contracted versions of meaningful phrases.3 It can be seen how “ta ho” is a contracted form of the French word taïaut from which Tally-ho probably derives; Tally-ho only begins to be used in England in the 18th Century.

Other uses of So Ho

The use of “So Ho” as a hunting cry appears in Shakespeare; In Romeo and Juliet, Mercutio say “So ho! What has thous found?” to which Romeo replies “No hare, sir”.

Also, it is thought that the cry gave its name to the district of Soho, London, as the area was previously used for hunting,. The Duke of Monmouth used “So Ho” as a rallying cry to his troops at the Battle of Sedgemoor in 1685.4

ROBIN

The suggestion that “Robin” on the legend is a generic name for a hound seems a lot more problematic. Where this is given as an explanation of the meaning, either at the PAS or elsewhere, no reference was given as a source for the idea.

Naming of dogs

Medieval hunting dogs were highly prized, particularly the greyhounds which completed the hunt and to which the hunting cry “So Ho” would have been given. These were high status animals and each dog was given its own name; Master of the Game describes how the handler must learn these. It also provides a list of over 1000 suitable names for a dog, which doesn’t include Robin.5 When Christies sold one of the 27 surviving manuscripts, (in 2006 for £198,400), they noted that in that version “Further names were added in a 15th-century hand, showing that it was consulted and used. Some refer to desirable qualities, like Stykefaste for a greyhound“.

In Livre de Chasse, Gaston refers to his dogs anonymously as “mon amy” or “douce”. In English manuals, where personal names do appear, the most frequent are Beaumond and Richier.7

Seals with the same legend

PAS record FAKL-82ADE2, CC By SA2.0

In a search of the PAS records, I found nine seals that had the same legend “SOHOV ROBIN” but with just the image of a hare (or rabbit).

An example is this seal found in 2021 and recorded at the PAS as FAKL-82ADE2.

It is difficult to see how Robin could refer to a dog that does not appear in the imagery.

Some explanations of the SOHOV ROBIN legend do suggest that Robin could be the name of the hound or the hare. In the two types of seal with the legend SOHOV ROBIN, the hare is either the only image or the main protagonist (riding the hound and blowing a horn). Hence, Robin seems more likely to refer to the hare than the dog.

Imagery of a hare riding a hound

Looking at the interpretation of the image of a hare riding a hound, it is useful to consider where else it appears and its meaning in those contexts.The image appears in medieval manuscripts and in other settings, as shown below.

Encaustic Tiles from the Friary, Derby

Pontifical of Guillaume Durand, Avignon, before 1390

stained glass of hare rstained glass at Great Gonerby church, Lincolnshire

Macclesfield psalter

The final image is from the Macclesfield Psalter, which was produced in East Anglia c 1320-30. 8 This contains numerous images from the “upside down world” in the marginalia. The intent of these is a matter of debate; a safe place for subversion against cultural norms, or as creative parody, intended to be humorous. 9

Use of similar imagery in religious settings

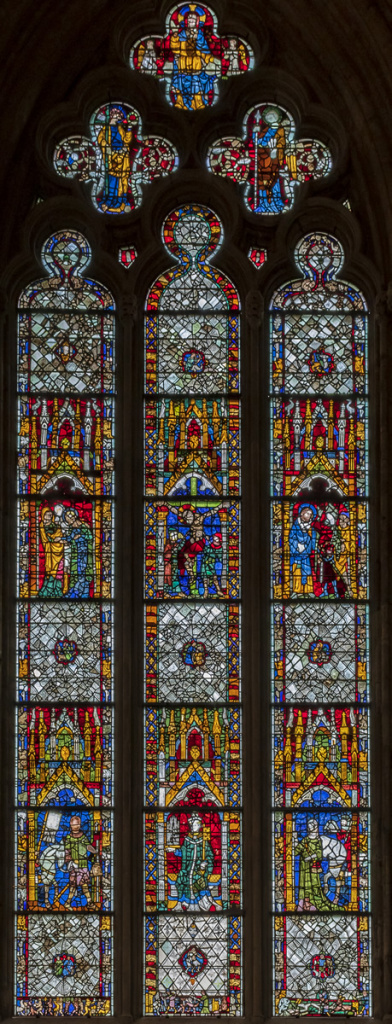

Images from the upside down world also accompany the crucifixion scene in York Minister’s famous Pilgrimage Window.

In an article on the imagery in the window, Roger Rosewell says “Closely resembling the bas-de-page illumination of an expensive psalter, the images include scenes of a fox preaching to a proud-looking cock; a funeral procession of monkeys with a monkey bell-ringer, cross-bearer, and four pall-bearers carrying a bier to which another monkey clings; a monkey doctor examining a patient; a parody of a hunt, with a stag chasing a hound” 10

Commenting in the same article, Dr Paul Hardwick, Senior Lecturer in English at Trinity and All Saints College, Leeds said “Although these images may appear as mere comic decoration, their intention was to reinforce the overall devotional message of the window. Like other examples, the York window needed a clerical interpreter to reveal its meanings.” .10

So, the image of a hare riding a hound appearing in a church setting indicates that it too had a specific meaning, which needs interpretation. That meaning would have been conveyed to the churchgoer; it is unlikely meant to be humorous.

Hares in medieval religion

To help understand the meaning, particularly in a religious context, it may be helpful to see how hares and dogs were portrayed in other religious works.

St Anselm

The biographer of St Anselm (1033-1109), Eadmer, tells how St Anselm encountered some dogs chasing a hare and provided refuge for it under his horse. This is interpreted as man (the hare) being protected from evil (the dogs) by the church (St Anselm). 11

Pilgrim hare

Pilgrim hare at St Mary’s Church, Beverley

This carving of a hare at St Marys Church, Beverley, was made sometime between 1330-40. It is dressed for a pilgrimage with its satchel over its shoulder bearing a scallop shell. 12

Incidentally, this carving is thought to be the inspiration for Lewis Carroll’s White Rabbit.

Use of the seal by the clergy

In the Durham Cathedral Archive: Medieval Seals is the record of William Greystock, rector of the Blessed Mary in the North Bailey, Durham having a seal design of “a hare riding on a dog and blowing a horn” from 1312-1317. 13

Interestingly, the bilingual inscription reads I RIDE ALONE A REVERE…

Other legends with the same image

The seal of William Greystock and others which bear the same image but a different legend might provide a further insight to the meaning of the imagery.

Below are such seals that I found on the PAS:

| PAS | Legend | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| NMS-8DCB04 | ALONE RID’ I HAV NO SA… | Alone I Ride I Have No Squire |

| HESH-4EF1A7 | SOHOV I RIDE | So Ho, I ride |

| HAMP-260CB4 | I RIDE | I ride |

| ESS-30ACC3 | DE PE SV PETIT CONV A hVM | ? |

| SWYOR-8FD7F6 | ALONE I RIDE HAV I NO SWAYNE | Alone I Ride I Have No Squire |

| NMS-ECAD95 | ALON I RIDE hAV NO SVA | Alone I ride [I] have no Squire |

Nearly all these legends use “I ride”. As it is the hare doing the riding in the image, the legend refers to the hare. This ties in with my earlier suggestion that Robin, in SOHOV ROBIN, refers to the hare and not the dog.

Also, some indicate that they have no squire, presumably as this is a new freedom; a role reversal with the previously downtrodden now getting the better of their former masters.

Meaning of the image

The religious meaning of the hare, particularly after St Anselm, is that it represents the common man, who needs the protection of god.

The upside down world of the hare riding the dog can be seen as that common man now getting the better of the thing or person that used to torment or dominate him.

My interpretation

Bringing these ideas together; the image can be seen to symbolise the little guy getting one over the establishment; there is also the sense of being a maverick or rebel.

Looking at the legend SOHOV ROBIN; So Ho was certainly a hunting cry but it may also have morphed slightly into an exaltation. Robin is the name of the little guy and so my interpretation of the legend is something like “Go little guy”.

The seal would therefore be well suited to someone who wanted to show that he had overturned the previous societal norms and was now making his own way in life.

Historical background

At the start of the 14th Century most English people worked in the countryside economy, controlled by local lords. The black death in 1348 rapidly killed about half the population and suddenly put labour in short supply. This put the peasantry in a much stronger bargaining position. Over the following few decades, their economic opportunities increased and some labourers took up specialist jobs that would previously have been barred to them.

Many of these would now need seals. The message of the hare riding a dog seal would be well suited to them.

Why Robin?

The question remains: Why the name Robin?

Robin was the nickname of Robert and Robert was a common name in the 14th Century. It was also a French pet name, used to show affection for a person or object. 14 It may be that it was used as pet name for a hare or common man (like an “average Joe”), although I can find no evidence for that.

Robin Hood

Here’s an alternative suggestion: Robin refers to Robin Hood.

Douglas Fairbanks as Robin Hood; a screenshot from the American film Robin Hood (1922).

Our view of Robin Hood is shaped by film and television, where he appears as person of noble birth. However, in the oldest known versions of the story he is instead a member of the yeoman class. In 14th-century England, where agrarian discontent had begun to chip away at the feudal system, he appears as an anti-establishment rebel.15 This all fits well with the meaning of the image and legend that I have suggested.

The earliest written reference to Robin Hood from William Langland’s Vision of Piers Plowman of 1377 is “Although I can’t recite the Lord’s Prayer, I do know the rhymes of Robin Hood“. This suggests that even uneducated men knew of Robin Hood and demonstrates that the legend must have been well known amongst all members of society by that time, regardless of their ability to read and write.

Then in Friar Daw’s Reply (c. 1402) a quotation of a later common proverb, “And many men speken of Robyn Hood and shotte nevere in his bowe” 16. This indicates how well established the stories of Robin Hood were and that people were keen to be associated with him, even if they did not know him directly.

Whether Robin Hood actually existed has been debated for a long time. It has been suggested that Robin Hood was a stock alias of thieves with the first known example being in 1262 in Berkshire. Alternatively, at least eight individuals have been proposed as being Robin Hood. Three of the more promising suggestions are Robert Hod, who was based around York, Robert Deyville in Ely and Robin Hood of Wakefield. 17

Distribution of finds

The map shows the location of finds recorded at the PAS of hare riding dog seals (blue dog) and hare seals with legend SOHOV ROBIN (brown hares) and locations of proposed Robin Hoods (red bows), mentioned above. By clicking on one of these symbols you can see the link to the PAS record.

It can be seen that there is some grouping of finds near the Robin Hood locations. An interesting aspect is that the hare alone seals only appear in the south.

Clearly the PAS finds are only a small sample of the many seals produced and there are some outliers and so the results do need to be treated with extreme caution. Also, the clusters could have been caused by other reasons; for example, the Macclesfield Psalter, with its image of a hare riding a hound, was produced in East Anglia.

Having said that, could the various local clusters be because each of them had their own local Robin Hood; the story that we now know being an amalgamation of their different stories.

Clearly, there’s a couple of leaps of faith here but could it be that detectorists, by their collective efforts, have solved the mystery of Robin Hood?

The answer, by the way, is probably not.

References

- Wikipedia: The Master of Game

- Project Gutenberg’s The Master of Game p229

- Animal-Human Bilingualism and Medieval Texts by Jonathan Hsy p24

- Wikipedia: Soho

- THE NAMES OF ALL MANNER OF HOUNDS: A UNIQUE INVENTORY IN A FIFTEENTH-CENTURY MANUSCRIPT by David Scott-Macnab

- Lot 501, EDWARD, DUKE OF YORK (c.1373-1415). THE MASTER OF GAME

- THE NAMES OF ALL MANNER OF HOUNDS by David Scott-Macnab p345

- Wikipedia: Macclesfield Psalter

- Gorleston Psalter ‘Virility’: Profane Images in a Sacred Space by Sarah J Biggs

- Vidimus: Monkey Business in the Margins by Roger Rosewell

- The hare and St. Anselm

- The Pilgrim Hare

- Durham Cathedral Archive: Medieval Seals

- Dictionnaire étymologique des noms de familles et prénoms de France, Librairie Larousse, Paris, 1980, Nouvelle édition revue et commentée par Marie-Thérèse Morlet, p. 523b.

- History.Com:The Real Robin Hood

- Dean (1991). “Friar Daw’s Reply” line 233

- Wikipedia: Robin Hood