Charles Masson, 19th century explorer, and a Roman ring

One of the fascinating aspects of detecting is that sometimes relatively mundane finds are connected with an extraordinary life.

One such find is this Roman period copper alloy ring recorded in the last couple of weeks at the PAS as DUR-89E5A6. It has been designated a Find of Note of Regional Importance. It may have been sitting in a detectorist’s collection for a while as the find date is given as 2005.

The hare is quite a common symbol in Roman jewellery and other artefacts and so this could be of British or continental origin.

British Museum collection

However, in their research the PAS recorder found some very similar rings in the collections of the British Museum. One of these is shown below.

Photo: The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

This ring fragment is part of a collection made by a Charles Masson which had been mostly acquired from the modern states of Pakistan and Afghanistan in the late 1830s.

The PAS record goes on to suggest that the found ring could have been collected by Charles Masson, or an associate of his, brought back to England and accidently lost.

The PAS record gave a brief summary of Charles’s extraordinary life, which I’ve expanded on below:

Charles Masson

Early Life

Charles Masson was an explorer, archaeologist and numismatist from the first half of the 19th Century. However, this was not his real name; he was born James Lewis in London in 1800. He was well educated, being versed in Latin and Greek and was fluent in French. At the age of 21, after a quarrel with his father, he enlisted in the army of the British East India Company and travelled to Bengal. His work involved depicting zoological specimens for publication. In January 1826, he fought at the siege of Bharatpur.

Deserting and travels

The following January he deserted and assumed the name Charles Masson. For three years he travelled around; across the Bikaner desert, on to Peshawar, through the Khyber Pass into Afghanistan before finally ending up at Bushire on the Persian Gulf. He convinced the EIC officials there that he was an American from Kentucky. They provided him with funds for archaeological research in Afghanistan.

Amassing a collection

In 1832 an anonymous witness in Kabul describes Masson as having “grey eyes, red beard, with the hair of his head close cut. He had no stockings or shoes, a green cap on his head, and a faqir or dervish drinking cup slung over his shoulder“.

Between 1833 and 1838, Masson excavated over 50 Buddhist sites around Kabul and Jalalabad in south-eastern Afghanistan. In 1833, he discovered the remains of Alexandria ad Caucasum, (one of the cities founded by Alexander the Great), on the plain of Begram, to the north of Kabul.

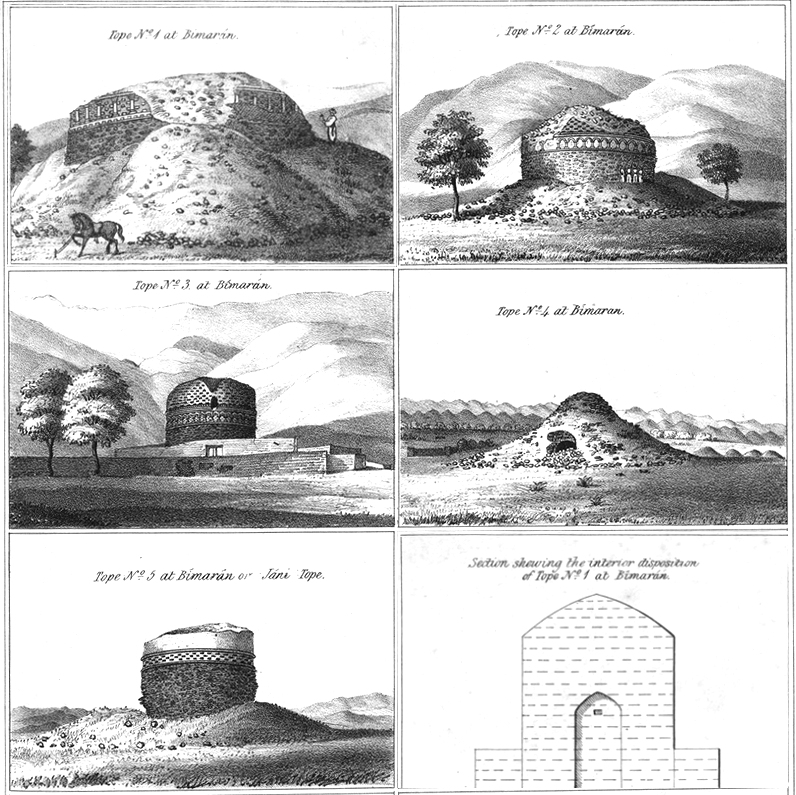

The illustrations are from Charles Masson book of 1841 “A memoir on the buildings called topes. In Ariana Antiqua: A descriptive account of the antiquities and coins of Afghanistan”

Masson’s collection grew from finds and purchases in the bazaars. It is estimated that he amassed up to 68,000 coins and about 9,000 artefacts. The British Museum has many of these, as well as his manuscripts, and has a Charles Masson project.

In the 1930s a French archaeological team in Afghanistan found some scribbling in a cave. It read ” If any fool this high samootch explore, Know Charles Masson has been here before“