William II

Death of William I

On 9 September 1087, William I, King of England and Duke of Normandy died, aged 60. He was buried in the abbey he had founded at Caen.

His second son, William Rufus ((known as Rufus because of his ruddy complexion) was always loyal to his father and raised a magnificent tomb over his grave.

Successor to William I

William I inherited the title of Duke of Normandy from his father, Robert the Magnificent. He was crowned King of England on 25 December1066, after defeating Harold at the Battle of Hastings.

When he died, William I had three sons, William Rufus, Robert the eldest and Henry, the youngest. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Lanfranc was the most trusted councillor of William I. He carried out the instructions spelled out to him by William I, as he lay on his deathbed.

William Rufus

King of England

To William Rufus went the throne of England.

Robert Curthose

Duke of Normandy

To Robert (known as Curthose due to having short legs) went the Duchy of Normandy.

William Rufus and perhaps Henry, too, had been with the Conqueror when he died but Robert was at the court of his father’s enemy: King Philip of France. Robert was rebellious at times and relations with his father had often been strained. It was only after Archbishop Lanfranc had pleaded his case that Robert was left the Duchy of Normandy.

Division of estate presents dilemma for nobles

Besides holding vast estates in England, the leading magnates also owned land in Normandy. When a single person was both King of England and Duke of Normandy the possibility of divided loyalty did not arise.

However, when the king was one man and the duke another, who would be obeyed? In matters English it would be the king and in matters Norman it would be the duke. But what if one of these men interfered with matters relating to the other? In such a case, if a magnate held land in Normandy and in England, then whose side should he be on?

The dilemma was summed up by the new king’s uncle, Odo of Bayeux, who is recorded as saying: “How can we give proper service to two mutually hostile and distant lords?”

Losers and winners

A change of king would lead to a change in fortune for some Norman barons.

Land taken from one baron to another

I mentioned when writing about William I that William Malet, who had fought alongside the Conqueror on 14 October 1066, had been entrusted with a disposal of the body of Harold II. Malet was eventually rewarded with the honour of Eye (several manors in Suffolk and elsewhere), which was one of the largest land holdings created after 1066. In 1086 it was worth £600 a year and extended into nine counties. William Malet died around 1071 and the honour of Eye passed to his son, Robert.

Robert Malet was sheriff of Suffolk and had been a councillor to William I. However, it would seem that he was out of favour with William II. The exact date is uncertain but quite early in the new reign the honour of Eye was given by the king to another Norman baron, Roger de Poitou.

This is an example of how a great estate could be lost simply because a king didn’t like one baron and wished to reward another. The ease with which a king could dispossess landowners would be a bone of contention for many years to come.

The coinage

The coinage of William II is very similar in appearance to that of his father. The weight and silver content are the same but the standard of striking is not quite as good as it was during the reign of William I. In some cases the letters are less skilfully entered into the dies and II can be A, H, M, N or V (for U); this can cause problems when trying to interpret the name of a mint and/or the moneyer. There are five types of pennies, each differentiated by the bust on the obverse and the design within the inner circle on the reverse. In addition, there is some doubt as to whether the last type of William I (BMC VIII) was in fact a coin of William II.

William I or William II BMC VIII

William II Penny, BMC I

William II Penny, BMC II

William II Penny BMC III

William II Penny BMC IV

William II Penny, BMC V

Over 60 different mints struck coins of William II. They are rarer than those of William I, which points towards a lower output of pennies after 1087. Most known specimens are from old collections or are single finds. Very few hoards have contained pennies of William II.

Revolts and expansion

Revolt by supporters of Duke Robert

In 1088 there was a revolt in England led by supporters of Duke Robert. However, after Robert failed to set foot in England, William II took swift and decisive action against the rebels and thereby secured his position.

Normans move into Scotland and Wales

Normans had now started to move slowly into Scotland and Wales and through a combination of bribery, diplomacy and military action the influence of the relatively new King of England spread. In 1089 William laid claim to Normandy and managed to gain the support of many barons. In 1095 Robert Mowbray, Earl of Northumberland, led a rebellion. It received little support from the other leading magnates and was soon suppressed.

Crusade called for by Pope Urban II

Due to a decrease of support through William’s plotting, by 1096 Duke Robert’s position had become precarious. He was glad to join the crusade called for by Pope Urban II. To finance this enterprise he pawned Normandy to his brother William for 10,000 marks (1,600,000 English silver pennies). At this time the crusading spirit was strong. Turks were pressing the Byzantine Empire and harassing Christian pilgrims. After an appeal from the Byzantine Emperor, Pope Urban called upon European powers to take the crusading cross.

Miniature of Peter the Hermit leading the People’s Crusade (Egerton 1500, Avignon, 14th century)

The first to answer the call was a monk named Peter the Hermit, who, with 20,000 followers mostly untrained in the art of war, set out from Cologne. Few of them managed to reach the Holy Land, as most fell victim to Turkish forces in Asia Minor.

However, four armies, each made up of around 10,000 men and led by great nobles, converged on Constantinople from France, Germany, Italy and the Low Countries.

No doubt the Byzantine Emperor was relieved when this great host moved on. There was hard fighting through Turkish held lands. On the Syrian coast the Crusaders met up with a fleet of ships commanded by an English prince – Edgar, great nephew of Edward the Confessor. On 14 July 1099 Jerusalem fell to the Crusaders. Godfrey de Bouillon was acclaimed as ruler and a mixed international body of knights would hold the city for close to a century.

Lands recovered and borders strengthened

From 1096 onwards, as well as being King of England, William was de facto Duke of Normandy. Land had been lost under the slack rule of Robert, so his brother set about regaining it. By 1099 he had not only strengthened the borders of Normandy but had also recovered Maine. This shared a border with Normandy and had been conquered by William I in 1063 but then lost to Hugh V in 1069. All this helped to reduce the problem of divided loyalties in both England and Normandy.

Some historical accounts describe William II as a pale shadow of his father. However, in military terms, in both England and in Normandy, he enjoyed a good deal of success. In diplomatic and political terms too, he proved to be able and wise, though cunning might better describe him. These are all things secular but in matters spiritual it is impossible to defend some of his actions.

William II and the Church

Some said that William II looked upon churches and abbeys as being establishments that he could plunder at will for the royal treasury. Most accounts of the period were written by monks, who were not afraid to point out the shortcomings of their king in terms of his attitude to religion. Amongst other things, some contemporaries accused him of blasphemy. A later historian even suggested he was a devil-worshipper.

What is certainly true is that he was very slow to appoint new bishops and abbots. At the time of his death in 1100, William I enjoyed the revenues of three bishoprics and twelve abbeys. Ranulf Flambard, previously a councillor to William I and advisor to Duke Robert of Normandy, became William II’s ‘enforcer’ of financial demands. For his expertise at wringing cash from various sources, Flambard was rewarded in 1099 by being made Bishop of Durham.

Lanfranc of Pavia, Archbishop of Canterbury

When he thought the situation warranted it, William I could be hard and ruthless. Nevertheless, he took religion seriously and interfered minimally in Church affairs.

In 1070 William I appointed Lanfranc of Pavia as Archbishop of Canterbury and the two men became close friends. William II behaved himself whilst Lanfranc was alive but in 1089 he died. Instead of appointing a new Archbishop of Canterbury, William II decided to appropriate for himself the revenues of the archbishopric.

Anselm of Bec appointed Archbishop of Canterbury

After Lanfranc died, the most outstanding figure in the Anglo-Norman Church was Anselm of Bec. He is said to have been admired and loved, even by his enemies. Everyone expected Anselm to be the next Archbishop of Canterbury. However, he did not want the office, as he argued he was too old and that he could not cope with the unruly son of William I. Then William II fell ill and believed he was dying. This coincided with a visit to England by Anselm in 1092-93. Thinking that his illness could be divine retribution for his irreligious actions, he begged Anselm to accept the archbishopric. Despite his misgivings, Anselm agreed to become Archbishop of Canterbury.

William II recovered and soon began to fall out with his new archbishop. Disputes between the two men were almost continuous. Anselm eventually decided that his position was untenable. He left England and spent the reminder of William’s reign either at the papal court or with the Archbishop of Lyons.

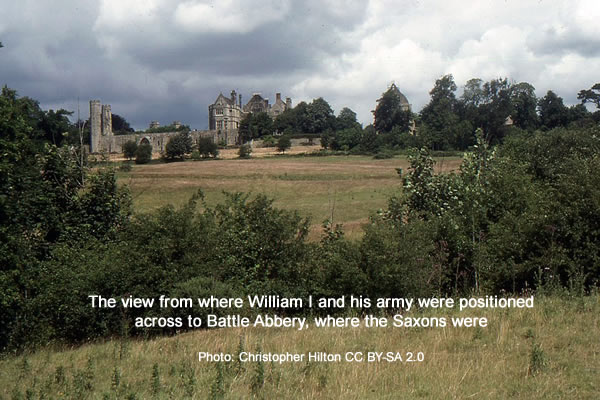

Battle Abbey

Having highlighted William II’s delight in appropriating revenues from churches and abbeys there is one exception. The monks of Battle Abbey (founded by William I on the site of the 1066 battle) remembered William II as a benefactor. The Conqueror had left its income in a somewhat precarious state but by adding endowments his son ensured that the abbey would be financially secure.

This may have had something to do with William II’s love of his father and/or the abbey’s link to the Norman Conquest. Whatever the case, at least one group of monks would look back on him with fondness.

The death of William II

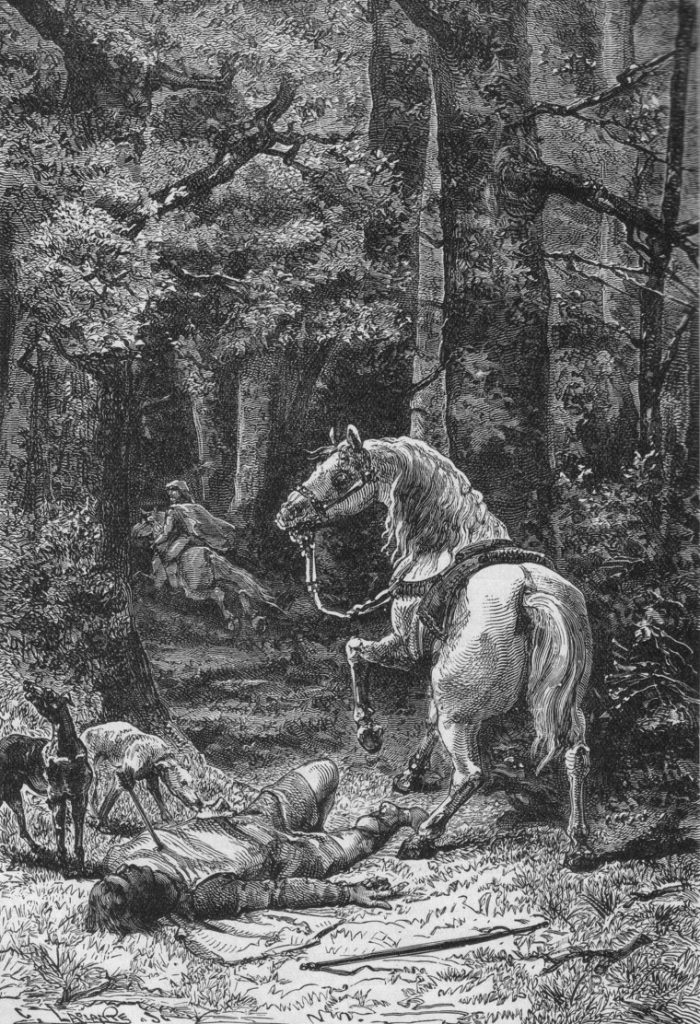

In the high summer of 1100, Robert was on his way back from the crusade and was about to marry a rich bride. This would have given him enough wealth to pay off the 10,000 marks he had received when he pawned his duchy to William II. But is that what William would have wanted? Or, having been in control of Normandy since 1096 and having strengthened it and retaken Maine, would William have wanted to keep it? We will never know what might have happened, for on the second day of August 1100 William was killed by an arrow whilst hunting in the New Forest.

William killed in a hunting accident

The death of William II is surrounded by controversy. The most prevalent account is that he was killed by an arrow shot by Sir Walter Tirel (there are several different versions of the spelling of his surname). William and a group of companions had ridden to the New Forest to hunt. The group split up to look for deer and William was accompanied by Tirel, who fired an arrow, which glanced off a stag and shot William – who died almost immediately. News of this occurrence spread very quickly.

Amongst those attending the hunt was William’s brother Henry, who galloped off to Winchester accompanied by some of his men to secure the royal treasure.

Henry succeeds William as King of England

Soon after the death of William I, his two eldest sons, Robert and William II, had agreed that one or the other should be the heir of whoever died first. Therefore, in 1100 Robert should have been the new King of England.

When Henry and his men reached Winchester, William de Breteuil pointed out that Robert was alive and should therefore be king. However, when Henry argued that he was the only son born after the coronation of William I of England, he was allowed to transport the royal treasure to London.

Mystery surrounding William’s death

Sir Walter Tirel’s wife was a Clare, his mother-in-law a Giffard – both of which were great families. After the death of William II members of both families were patronised by Henry. One became the Earl of Buckingham, a second the Abbot of Ely, and a third gaining the bishopric of Winchester, which was the richest of all the English sees. Tirel fled straight after the death of William II and gained nothing from it. However, it has been suggested that he might have been a tool of the Clares and the Giffards. They could have been hoping that they would benefit if Henry gained the throne.

The Rufus stone, which is claimed to mark the spot where William II fell, was inscribed in 1789 “Here stood the Oak Tree, on which an arrow shot by Sir Walter Tyrrell at a Stag, glanced and struck King William the second, surnamed Rufus, on the breast, of which he instantly died, on the second day of August, anno 1100“.

The Rufus Stone, near Minstead, claimed to mark the spot where William fell.

Had it been thought that Tirel purposely killed William then it is likely that his faithful knights would have sought revenge and hunted him down. That this didn’t happen raises doubts about his death. One chronicler wrote that William himself shot the arrow, which killed him when it was deflected. Another account says that he fell onto an arrow. Tirel is reported as saying he was in another part of the forest when William was shot. This was said when Tirel was on his deathbed, a time when he was likely to tell the truth. Therefore, whilst it is certain that William was killed by an arrow, the circumstances surrounding this event will forever be shrouded in mystery.

William II, 1087-1100

It could be argued that William II was lucky to gain the throne of England. Had his older brother Robert been on better terms with his father then he might have inherited the throne of England as well as the Duchy of Normandy. However, Archbishop Lanfranc saw to it that the dying wishes of William I were carried out.

As already mentioned, contemporary accounts paint William II in a bad light. This is only to be expected, as most were written by monks whose religious institutions were robbed of cash by the king. Most historians, too, have little good to say about the second Norman King of England.

That he was irreligious cannot be denied. However, he held England together, secured Normandy, strengthened the Exchequer by siphoning off revenue from churches and abbeys, and reigned over a period during which royal authority remained strong. Therefore, like many other kings who followed him, there were good and bad aspects to his overall character.