“Tealby” penny of Henry II

Tealby pennies of Henry II are reasonably common detecting finds and we have had a few sent into this website. It is probably the worst struck of any English coin. Examples as bad as this find show how bad the striking of the coins could be. They do however provide an interesting challenge in trying to identify the mint and moneyer. As in this case, it may not be possible.

It’s a good opportunity to have a look at historical background of these coins and the discovery of the hoard that gives them their name today.

Historical background

Unlike continental Europe, the minting of coins had been a royal prerogative in England since at least 973. The Anarchy that proceeded Henry II’s range broke this with issues by Empress Matilda and various barons. These caused concerns about the reliability of the coinage which in turn affected the economy.1 William of Newburgh, the 12th century chronicler, said “in England there were in a sense as many kings, or rather tyrants, as there were lords of castles. Each minted his own coinage, and each like a king had the power to lay down the law for his subjects“.

After the Treaty of Winchester of 1153, which brought the Anarchy to an end, coinage was included in the restoration of a unified national administration. The issue of the “Awbridge” type pennies of Stephen was the result. When Henry ascended the throne in the following year, he had many other things to deal with and continued with this coinage, carrying Stephen’s name for four years.

In 1158 began the first of two reforms of the coinage which resulted in the introduction of the “Cross and Crosslets” or “Tealby” pennies. There was a radical reorganisation of the mints and a wholesale replacement of the moneyers, with possibly only 9 remaining from the 100 who had produced the Awbridge pennies.2 This may well be the reason for the poor quality of workmanship of the Tealby coins. In his classification work, the famous numismatist, L. A. Lawrence said “The whole issue of this coinage, speaking generally, is exceedingly badly struck, though the dies would appear to have been well made“. Also, the fineness and weight of the silver was usually good.

Tealby Hoard

As many detectorists will know, Tealby coins get their name from the discovery of some 6000 coins found at Tealby, Lincolnshire in 1807. There’s a curious trail of events that led the better specimens ending up in the British Museum.

George Tennyson

A ploughman found an earthenware pot (described as Roman, although some dispute this) at the side of a road which crossed a ploughed field.

The ploughman was employed by George Tennyson who gave him the find. George was grandfather of Alfred Lord Tennyson, who wrote “Charge of the Light Brigade“.

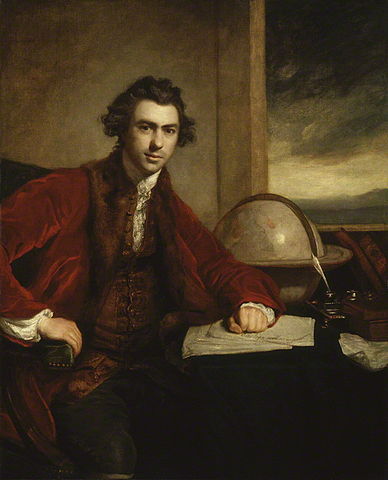

Sir Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks was a naturalist who took part in James Coo’s first voyage to Australia and later became president of the Royal society. He became a close confidant of George III and advised him on various matters including currency. He heard about the Tealby hoard while staying at Revesby Abbey, some 20 miles south of Tealby in the autumn of 1807.

He oversaw their disposal and rendered an account to George Tennyson on 27 August 1808.

| Melted at the Tower | 5127 |

| Disposed of to collectors | 277 |

| Reserved as a specimen of the general condition of the collection | 20 |

| Remains undisposed of | 273 |

| Collection delivered by Mr Dryander to Mr Tennyson | 34 |

| Total | 5731 |

Tennyson received a total of £99 15s 11d for the coins; some £64 for the ingot from the 5127 melted coins and £34 for the 277 sold to collectors.4

Sarah Sophia Banks

The reason that Joseph Banks oversaw the disposal of the hoard was probably because his devoted sister, Sarah was, according to one source “the most noteworthy female collector of coins and tokens this country has known“4

Of the 277 coins bought by collectors, Sarah acquired 172. These were the “best specimens of all the varieties of towns and mint masters” and Sarah’s detailed accounts record the mints and moneyers for the coins in her collection.

On her death in 1818, 104 coins went to the British Museum and replaced poorer examples that they held at the time. The remaining 68 went to the Royal Mint museum.

References

- English mint administration, moneyers and monetary reform in the reign of Henry II, 1154–1189. Gilbert M Stack, 2004.

- Henry II: New Interpretations. Christopher Harper-Bill, Nicholas Vincent. 2007Copyright Date: 2007

- ON THE FIRST COINAGE OF HENRY II. L. A. LAWRENCE., F.S.A 1918

- SARAH SOPHIA BANKS AND HER ENGLISH HAMMERED COINS, R. J. EAGLEN